CNN

—

His golf course design business flourishing, Bobby Weed was sailing smoothly into the turn of the century. Gradually, and then suddenly, he and his family lurched into uncharted waters.

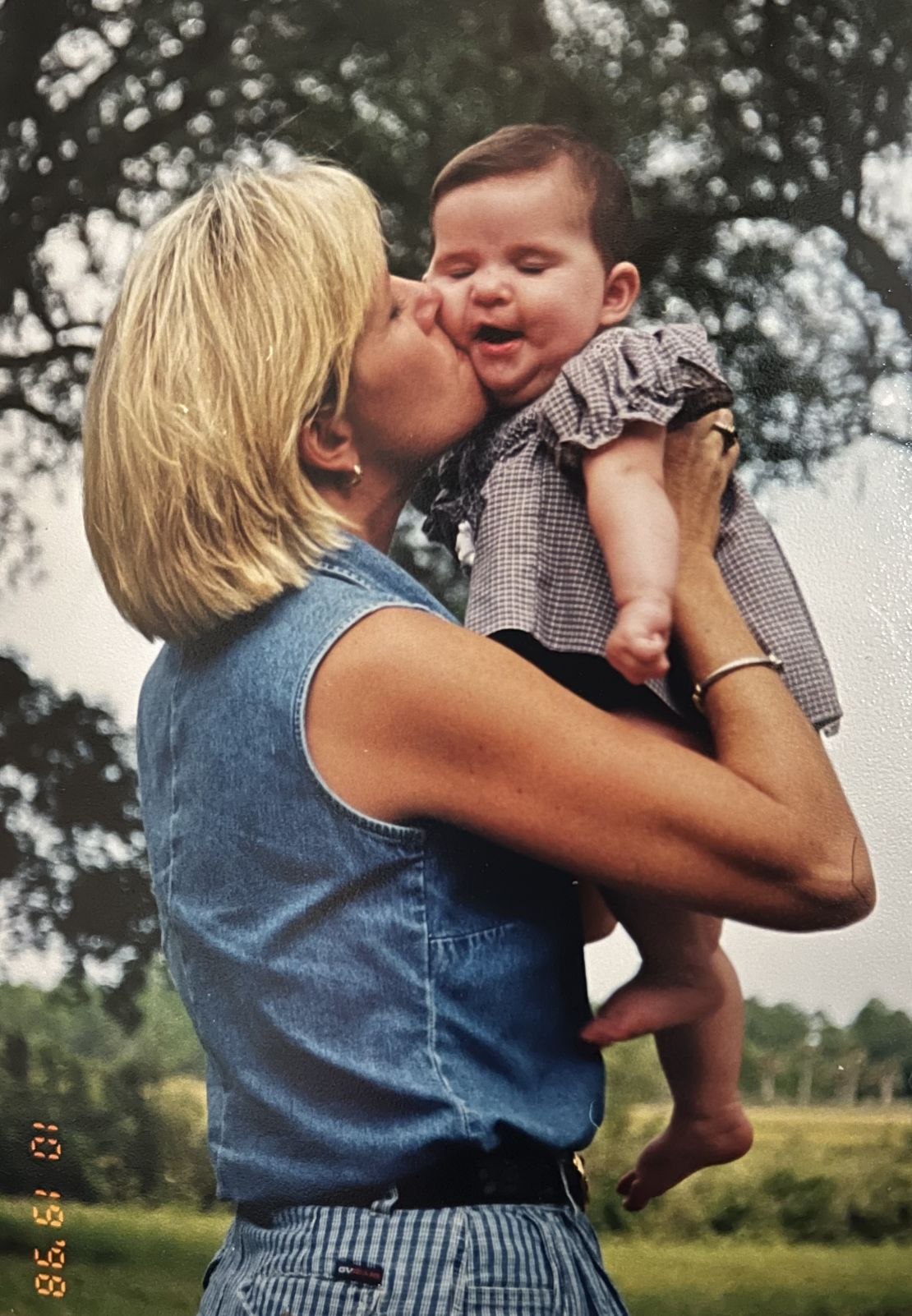

Born in 1998, Lanier – the youngest of Weed’s three daughters – stopped walking and talking at 18 months old. Shortly after, she was diagnosed with nonverbal autism.

“You know when you go up to an electrical panel and just start hitting the breakers and turning them off? That’s about what started happening with her,” Weed recalled to CNN.

With 1 in 36 children – about 2.8% – identified with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in 2020, according to estimates by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), awareness and understanding of the developmental disability is rising. Yet when Lanier was diagnosed, Weed and his wife Leslie, who lived in Ponte Vedra Beach, Florida, found themselves plunged into a world far less educated.

In 2000, just 1 in 150 children were identified with ASD by the CDC. Combined with the fact that the condition is almost four times more common in boys than girls, it meant that Lanier’s case was even more unfamiliar to professionals and Weed alike at the time. The family found themselves in “uncharted territory,” Weed said.

“We didn’t even know what autism was,” he added. “We had to pretty much teach and train ourselves.

“It changed our lives. It changed our family … We immediately felt like we were in a canoe crossing the Atlantic by ourselves, and everybody else was on a big ship. It was really, really difficult – challenging in every way.”

“I didn’t know I had such a warrior wife”

A frenzied search for support saw Weed jetting to specialists across the US, while his wife immersed herself in learning as much as she could about autism – so much so that Weed recalled her attending conferences and being mistaken for a doctor or an attorney.

Such a dogged pursuit caused significant upheaval. Weed’s two other daughters – Haley and Carlisle – were sent to boarding school to spare them the “total chaos” enveloping the house, as a flurry of doctors, therapists, and specialists came through the door. At one point, Weed had six people employed to help assist Lanier, he recalled.

Strains were felt financially, with Weed – all-the-while boarding long flights for various course design projects – feeling “like a human ATM.” Then, there was the potential impact on his marriage, yet the experience only served to bring he and his wife – who first met on a golf-related blind date – closer together.

“It showed me a side of my wife that I didn’t know existed,” Weed said.

“I didn’t know I had such a warrior wife and that she was in the trenches 24/7 … It was a challenge like no other. I could see it was a massive divorce rate in association with autism but, from my perspective, it actually strengthened our marriage and it strengthened our family overall.”

Enrichment

Determined to share what they had learned with other families in Northeast Florida navigating similar challenges, in 2004 the couple created the Helping Enrich Autistic Lives (HEAL) Foundation to educate and fund services for those affected by autism.

The foundation has since raised over $5 million in support of the local autism community, providing annual Spring and Fall grants to various associated organizations and funding $500,000 for public and private school education enhancements for ASD students.

They have funded the training of autism service dogs, as well as the delivery of over 500 iPads and 200 tricycles to students with special needs, and bankroll a series of summer camps, including Help Us Golf (HUG) Camp.

Staged at TPC Sawgrass in Ponte Vedra Beach, Florida – site of The Players Championship and among Weed’s most famous projects – the summer camp sees local PGA pros assist in teaching the game to children with autism. Though it offers the chance to play the iconic 17th Island Green, learning to swing a club at one of the world’s most well-known courses is just one part of the experience.

“It’s a wonderful camp that goes much further than just golf,” Weed said.

“They show them all the wildlife associated with the golf course, all the water features, show them how to change the cups on the greens, how all the grass gets mowed. It becomes so educational.”

TPC Sawgrass has been a recurring spot for the foundation ever since it hosted a 2007 Gala in celebration of the PGA Tour choosing HEAL as its “Adopt-A-Charity” recipient – choosing the foundation as its sponsor for a tournament at the course.

Having worked for the PGA Tour for 13 years before leaving to start his own design firm in 1996, Weed’s contact book within the game is bursting at the seams. Several of the biggest names he’s associated with have offered support to the foundation, including design mentor Pete Dye and seven-time major champion Arnold Palmer, who Weed says once offered his private plane to allow him and Lanier to fly to see a specialist in Chicago.

And as Weed, who also designed Michael Jordan’s private golf course in Hobe Sound, continues to shape courses around the globe, most weekends are spent with his youngest daughter, now 25.

Lanier lives in a nearby residential group home, which offers round-the-clock support for adults with autism.

“It’s been good for our daughter and it’s been good for us,” Weed said.

“We see our daughter every weekend, we have access to her, and there’s a bit of a comfort level knowing that she’s safe, she’s secure, that we can coexist together, and that we’re still family.”