CNN

—

When an elite group of athletes crouch into starting blocks at Paris’ Stade de France this weekend, their bodies tense with adrenaline and anticipation, it’s hard to ignore that the next 10 seconds could define their lives and careers.

Few sporting events command the attention of the world like the men’s and women’s Olympic 100-meter finals, and few place such an intense weight of expectation on an athlete.

How do you silence your nerves when a hush descends on the stadium? How do you quieten the mind when an audience of millions is about to watch the biggest race of your life?

“I think it was the worst pressure you could ever be put under,” British former sprinter Allan Wells, who won 100m gold at the 1980 Moscow Olympics, told CNN Sport.

“You run through it in your head thousands of times – the start, the gun going off,” Wells added. “I think it’s the apprehension of what’s going to happen – you’ve got to get a good start … you’ve got to get into your running as quickly as possible.”

Professional sprinters, of course, are accustomed to performing in this kind of environment. The art of exiting a starting block, thighs pumping and elbows driving, is one to which they have devoted many hours of painstaking practice.

But at the Olympics, the stakes are higher than ever before. This is, after all, the most-watched event of the fortnight, with an audience of 35 million tuning in for Usain Bolt’s victory at the 2016 Rio Games on NBC.

An error here could be disastrous. Take British sprinter Zharnel Hughes, for example, who was disqualified from the 100m final in Tokyo three years ago for jumping out the blocks too soon. He later attributed the mistake to cramping in his calf, explaining in a social media post how the pain of disqualification “cuts real deep.”

It’s a fate that every athlete in the men’s and women’s races this year – most of all Hughes – will be desperate to avoid as they aim to keep their nerves and emotions in check on the start line.

“It was the worst feeling you could ever have but still be in control of what you were hoping to achieve,” said Wells, one of only three British sprinters to win 100m gold at the Olympics. “Put me in that situation right now, today, and I think I would just have a heart attack.”

For Olympic sprinters, mental preparation is just as, if not more, important than how they prepare physically.

The legendary Bolt, winner of three consecutive 100m gold medal between 2008 and 2016, said that he would try not to overthink things.

Bolt was famously relaxed on the start line, fist-bumping race officials and playing up to the crowd with gestures and poses. To distract himself before a race, he has previously said that he might think about playing video games or what he would have for dinner that evening.

02:56

– Source:

CNN

For some, the challenge is in remaining calm while also being entirely focused on the task at hand.

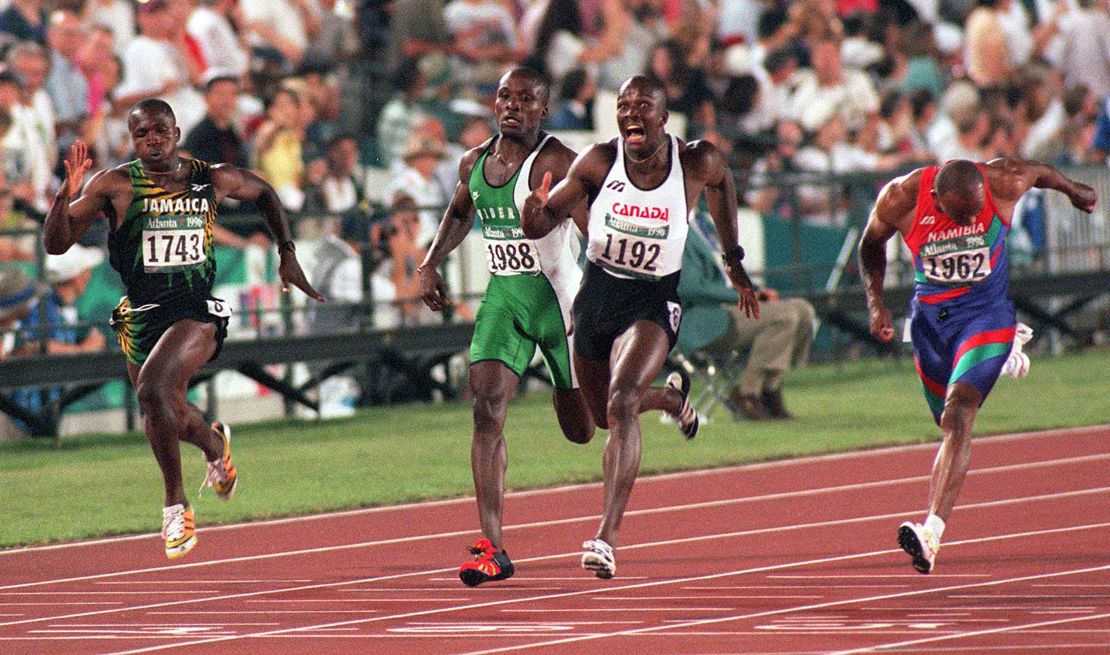

“A combination of utmost power and utmost relaxation while the entire world is watching – that is really what’s in front of you,” Donovan Bailey, Canada’s 1996 Olympic 100m champion, told CNN Sport.

“You have to embrace all of those things and be completely at ease and totally relaxed. Sometimes I try to tell athletes, ‘Imagine yourself just sitting in your living room watching TV.’ That’s actually what it is. And it’s as simple as that.”

Bailey ran a record-breaking time of 9.84 seconds when he won gold in Atlanta to become the reigning Olympic champion, world champion and world record holder.

Never short on confidence, never questioning his ability, Bailey thrived on the biggest stages, famously orchestrating a one-on-one race over 150 meters against Michael Johnson in front of a TV audience of millions.

“When the light was shining brightest, I was always at my greatest comfort,” he said. “And so any of the athletes I consult with now, regardless of where they are from around the world, I tell them, ‘You have to embrace who you are.’”

Each athlete, then, will have a different approach to big races.

American Noah Lyles, for instance – one of the favorites to win gold this weekend – likes playing to the cameras. Before competing at the US Olympic trials, he pulled a series of rare Yu-Gi-Oh! cards out from under his sprint suit as a nod to his love for anime.

“Noah loves the crowd,” Jo Brown, a physio and performance coach who has been working with Lyles, told CNN Sport. “That’s easy for him at the big events. He doesn’t like the smaller meets as much; he likes a big crowd.

“We had a conversation once. I was like, ‘Oh, what music did you put on to help you fire up?’ And he goes, ‘I don’t actually perform well fired up, I perform best when I’m happy. Music can be a really big part of the build-up and the planning of the day and what songs you have on your playlist.’”

According to Brown, Lyles might listen to The Bee Gees – known for their upbeat dance hits “Night Fever” and “Stayin’ Alive” – before a race. Other athletes, she’s noticed, prefer a different tactic.

“Some people, you’ll see them getting really fired up, getting really aggressive,” said Brown. “They’ll beat their chest and they want to bring anger – anger is that emotion that they essentially bring to the fight.

“Their self-talk in their head might be something about ‘get in the fight,’ or whatever it is that they need to do that is a trigger for them.”

Having worked with elite athletes across several sports, Brown is acutely aware of the way in which pressure can influence performance. With sprinters, she would guide them through visualizations in the days before a race, laying out how they want to think and feel while coiled up in the starting blocks.

“In the 100 meters, the body, yes, we need to have it primed and we go through specific activation strategies. … But I think it’s actually more about what the mind can do to really stay in the race in those first few meters,” said Brown.

“To execute your best performance, my question to anyone is: Have you done everything in your power to execute your best performance in the moment today? And if you’re standing behind the blocks in the Olympic Games and you can answer that question and go, ‘Yes, I’ve done everything in my power to execute my best performance today,’ all you have to do is do at that point.

“The 100 meters, 100% it’s a doing race. … The whole idea with visualization is that, by the time you actually go to execute the race, you’ve already done all the work mentally and physically. At that point, you don’t have to think, you have to do.”

Although Lyles is the favorite to win the men’s 100m final on Sunday, a handful of runners – Jamaican duo Kishane Thompson and Oblique Seville, as well as Kenyan Ferdinand Omanyala – have run similar times to the reigning world champion this year.

His teammate Sha’Carri Richardson has the fastest women’s time this year and will face competition from Jamaican Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce, who will end her decorated career after the Olympics.

But the 100m is not always a straightforward event to predict. For Bailey, both the men’s and women’s races are “wide open” this year, especially in the high-pressure environment of an Olympic final.

“It’s going to be the person who’s most prepared mentally, physically and psychologically,” he said. “In every single way, you have to be the most disciplined human being in that field.”