CNN

—

Roald Bradstock can remember the exact moment when he began to feel unwell.

The former Olympic javelin thrower’s resting heart rate suddenly surged to a frightening 200 beats per minute last year, triggering an unusual first instinct: His first thought wasn’t about trying to save his own life, it was instead to preserve his own legacy. He immediately rushed downstairs and began signing his name on his artwork – just in case.

A short time later he was lying prone on his living room floor as paramedics worked to stabilize him. He’d suffered a mini-stroke, and he almost went into cardiac arrest in the ambulance.

Fortunately, he survived to tell the tale – and create more of the artwork he so quickly thought of in the heat of the moment.

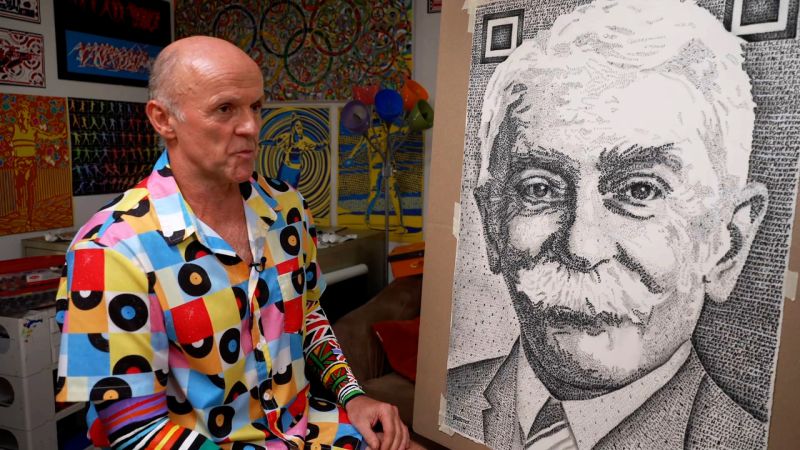

Dubbed the “Olympic Picasso” by the British Hammer thrower and commentator Paul Dickenson almost 20 years ago, Bradstock – who competed in the 1984 Los Angeles games and in Seoul four years later – spent many years fighting for recognition and acceptance. He recently seems to have finally found it.

In June, his work, “A Race Against Time” was featured alongside art world legends like Rembrandt, Rodin, Andy Warhol and Banksy in a weighty French tome called “Le Sport dans L ’Art” (Sport in Art). A month earlier, he and five other Olympic and Paralympic athlete artists had been profiled in the French magazine Beaux, a feature that referenced his work spearheading the revival of the Olympic artist movement.

From 1912 until 1948, Olympic competitions featured art competitions in architecture, literature, music, painting and sculpture, and the modern Olympic Movement’s founder – the French aristocrat Pierre de Coubertin – awarded medals for creations inspired by sport. Since 2018, Bradstock has been helping the IOC reignite the movement with an Artists in Residency program; he’s the only athlete to have been involved in three games as an artist.

It’s almost as if the arts and athletics were destined to collide in Paris in 2024. Exactly 150 years ago, the French capital staged the first ever exhibition of the Impressionist Movement and it’s exactly a century now since Paris last staged the Olympics.

“I wasn’t planning on it, it just materialized,” Bradstock said. “I cannot believe it. I was like, ‘Wow, how did this happen?’

“I didn’t realize how much French artists and French movements had really influenced me as an artist. My goal was always to promote sports [art] as a legitimate subject matter. And I’ve overshot it and created this new genre – Olympism.”

Bradstock says that as his popularity has grown, he’s stopped selling his work because he’s afraid of undervaluing it but he’s still forging ahead with creating. He’s spearheading a new movement of Olympic artists, a group he estimates to be roughly 1,000-strong, with ambitious plans to bring the two pursuits even closer together in time for the Los Angeles games in the summer of 2028.

The connection between art and athletics

Bradstock first made his name as an Olympic javelin thrower for Great Britain, finishing seventh in 1984 and 25th in 1988. Having developed an unusual technique to work around his spina bifida birth defect, his longevity was remarkable –Bradstock was still going decades later, when he was 50 years old, finishing second in the Olympic trials for the London Games in 2012.

He was impossible to miss, often competing in patriotic, flamboyant clothing that he’d painted himself. He quite literally wore his art on his sleeve.

One might assume that Bradstock discovered art as a second career, but he admits that he has always been as equally passionate about the tip of his paintbrush and the point of his javelin.

“They’ve been neck and neck my entire life,” he explained to CNN Sport, “and I’ve always kind of struggled because I don’t like doing anything halfway. I thought they were different, and when I realized that they were the same then everything kind of clicked.”

Instead of focusing solely on an athletic career, he left the UK to study at Southern Methodist University in Texas, juggling his time between the track and his easel. But he admits that he’s always been something of an outlier, finding acceptance hard to come by in either community.

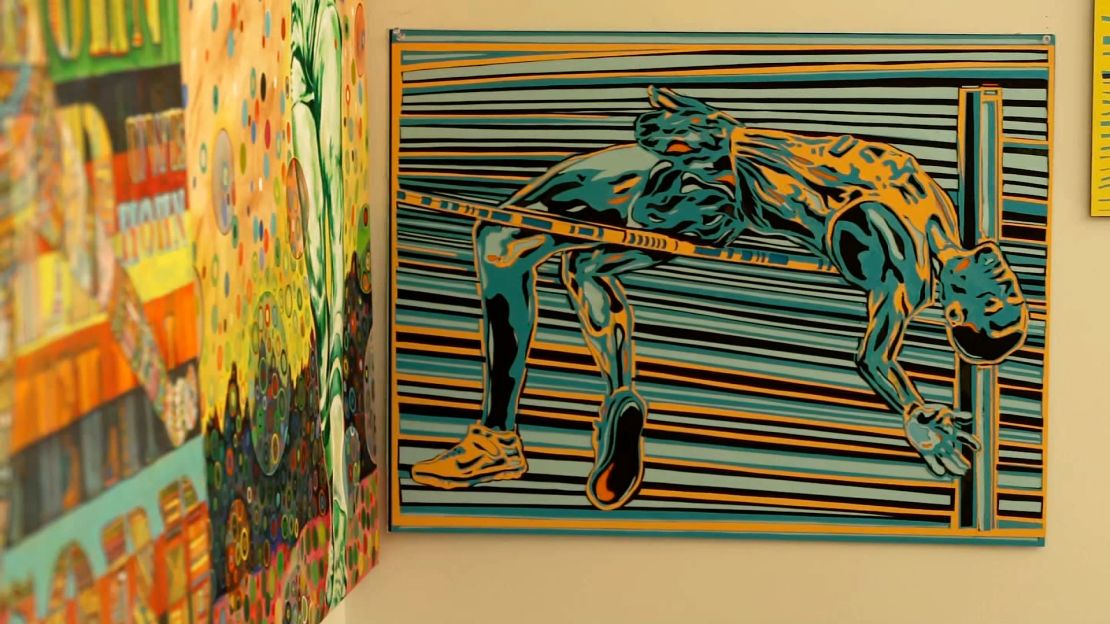

Bradstock’s portfolio of work is bursting with energy, movement and color. He’s spent decades trying to capture the essence of athletic endeavor and the values and spirit of the Olympics. Repetitive lines are a feature of his work, crafted to symbolize the interminable practice and commitment in the pursuit of excellence. It’s a style which has helped him connect the dots between his two passions.

“Because people equate time with value, the first question they ask me is, ‘How long did that take?’ And for both athletes and artists, the general population doesn’t see all the work that goes into it.” So lately, when discussing how long it has taken him to create a piece of art, his answer goes something like, “37 years, five months and two days.”

He says that athletics helped prepare him to be an artist in ways that he would never have considered.

“My athletic career was preparation for my artistic career,” he said. “Failure is part of the journey. You know, the rejection and the frustration. Olympic athletes are trained to be very goal-oriented, to overcome obstacles, to be creative. And even if you don’t think you’re a creative, elite athletes have to be creative in order to figure out how to work around injuries and such. There’s definitely a kind of crossover.”

Leaving a legacy

Both can be challenging, but he’s come to the realization that art brings him more peace and fulfilment that than athletics ever could.

“The physical part (of being an athlete) is a given, everyone goes through that. I think the hardest thing for me was the mental part, the stress of getting close to a competition. On the other hand,

“I can’t really think of any bad days as an artist,” he added. “Even when I fail. I’m pushing myself. I’m creating a jigsaw puzzle and solving it at the same time. I’m thrilled where I’m at.”

There’s an objectivity to sport that nobody can deny – fastest, highest, strongest always wins. But art is so much more subjective, sometimes painfully so.

“The greatest insult to an artist is indifference,” Bradstock explains. “I’d rather have somebody vomit next to my work than ignore it.”

At the age of 62, he’s moving on from last year’s health scare, but he knows that one day he will be gone, and his art will be his legacy. So how would he like to be remembered?

“I don’t know,” he pondered. “If I was remembered for being creative, for pushing the boundaries, for creating events and activities that show athletes are not one or two dimensional, that there’s more to us.”

But then he settles for something a little less lofty: “Just to be remembered, period,” he chuckled. “That would be good for a start!”

Perhaps it means more to him that he’s finally lived up to the dream of his late father, a linguist and interpreter in the Second World War.

“He was always a big supporter of my Olympic career and supportive of my artistic abilities but was a little frustrated that I didn’t take to other languages,” he said. “I think he’d be delighted and proud that I’ve managed to combine the two universal ‘languages’ of sport and art into one – an idea the visionary Pierre de Coubertin had when he brought back the modern Olympic Games!”