CNN

—

Beyond the towering rolls of barbed wire, the world was on fire — continents ravaged, a death toll spiraling into the millions. Inside the fence, captured allied soldiers practiced their putting.

It was the Nazi Germany prisoner-of-war (POW) camp from which arguably history’s most famous break-out was sprung, yet less well-documented is that before — and even after — “The Great Escape,” Stalag Luft III was home to one of the most improvised and ingenious sports clubs ever created.

Eighty years ago, golf went to war.

Fear and hunger

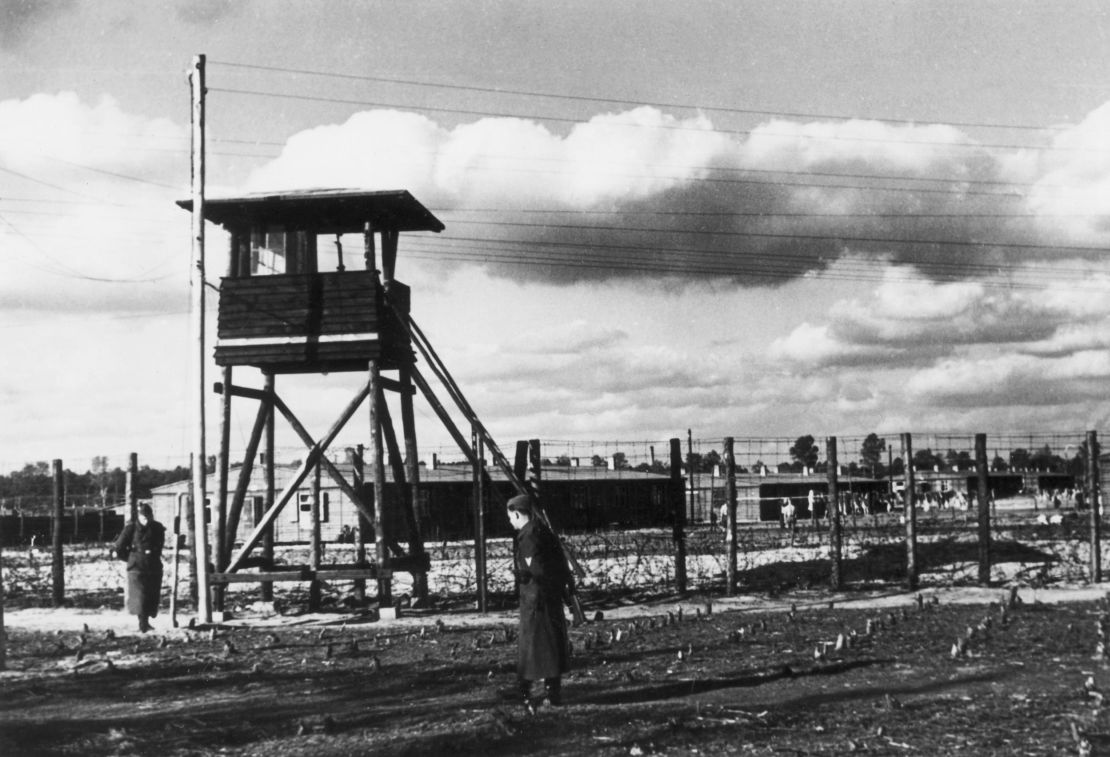

Established in the Spring of 1942, three years into the Second World War, Stalag Luft III was a camp run by the German air force, the Luftwaffe, around 130 miles (209 kilometers) southeast of Berlin near the town of Zagan, in what is now Poland.

Initially intended to hold British Royal Air Force (RAF) pilots, the remote camp would later detain a mass of United States Army Air Force personnel and an assortment of pilots from other Allied nations, ranging from Norway to New Zealand. Constantly expanding, the base held just shy of 11,000 prisoners at its peak.

In comparison to other POW camps under German control, captives at Stalag Luft III received “excellent” treatment for the majority of the war, according to a 1944 US Military Intelligence Service (MIS) report. Camp guards — either those deemed too old for combat or young men recuperating from long service or injury — mostly adhered to Geneva Convention rules. The air force POWs’ status as officers further helped their cause, and meant they were never required to work, though they did assume many daily chores.

Yet camp life was by no means a stress-free sojourn from the front line. With many prisoners captured within the first years of the war, boredom and restlessness were endemic. Dementia set in for some prisoners, who were then removed by guards and later reported to have “died of pneumonia,” wrote John Strege in his 2005 book on golf during the conflict, “When War Played Through.”

Mental anguish frequently spliced with the physical pain of near-constant hunger, with captives forced to self-ration a combination of small Red Cross parcels — containing canned food, powdered milk and other items — and camp meals, formed mostly of stodgy bread and thin broth.

Much of this history was preserved by Pat Ward-Thomas, an RAF pilot captured after being shot down over the Netherlands, who detailed the camp experience in letters home during his confinement.

For Victoria Nenno, senior historian at the USGA Golf Museum in New Jersey, Ward-Thomas is very much “the main character” of this story.

“He captures the tenor of the place; the discomfort, the hunger, the fear, the confinement,” Nenno told CNN.

Tee off

Prisoners did have some powerful weapons to call on in their battle against boredom, and many of them centered around sport.

Boasting what the MIS report described as “the best organized recreational program” of any American camp in Germany, captives had access to an athletics field, volleyball courts, and a pool — albeit filthy and technically on reserve for fighting fires — that could be swum in. The wealth of sporting options, including fencing and basketball, was supplemented by an impressive arts program, with prisoner-organized musicals and orchestral performances arranged in makeshift theaters.

Yet curiously omitted from the MIS report is any reference to arguably the camp’s most passionate pastime, born in early 1943 when captured RAF pilot Sydney Smith ripped open a Red Cross parcel to discover an iron golf club.

Short, and with a hickory shaft, it was far from PGA Tour standard — but its new owner was enchanted. Smith carved some nearby pine into a sphere and wound it with wool and cotton before layering it with cloth and stitching it together to produce the first of countless homemade balls manufactured at Stalag Luft III.

The sound of club striking ball from between the barracks may as well have been a dinner bell for avid golfer Ward-Thomas, who — soon followed by other prisoners — approached Smith for a piece of the action. The camp’s first golfer would share his club, but never his ball, and so the great ball production line began.

Taking anywhere up to six hours, the increasingly elaborate crafting process became something of a “contest” between captives, according to Strege’s book.

Rubber was so crucial that budding players requested that quarterly clothing parcels included tobacco pouches, gym shoes and air cushions. The rubber from such items would wrap around the core and then be cased within leather stripped from shoes — a process eerily reminiscent of “featheries,” some of the earliest post-wooden golf balls ever made.

“These men unknowingly created equipment that was very similar to what they were using 300 years before,” said Nenno.

“The creativity from such scarcity … You put all of these smart men in a confined space with nothing to do and you’d be not only surprised, but amazed, at what they’re able to create because of that situation.”

“Truth is stranger than fiction”

Eventually, 10 iron clubs arrived, sent by Ward-Thomas’ Danish pen-pal. Before that, clubs were made by POWs through similar feats of ingenuity.

Foil collected from cigarette packets was melted using a makeshift blowtorch —twisted tin lit with the aid of rendered margarine — into a mold to make clubheads, which were then fitted to whittled strips of wood with a cloth for grip.

Equipment sorted, “Sagan Golf Club” — named after the nearby town — was founded mere weeks later. At the inaugural “Sagan Open” prisoners simply competed to get their ball nearest to a designated tree, but later a nine-hole, par-29 course was constructed.

Winding some 850 yards around camp building and over the pool, the course “greens” — grass removed of stones and roots before being smoothed with yellow sand — had powdered milk cans wedged into the ground to act as holes.

Shots often sailed out of bounds into the “forbidden zone” just inside the barbed wire fence, throwing up a potentially life-threatening dilemma: lose a ball that took six hours to craft, or risk getting shot as an assumed escapee by a trigger-happy guard?

A solution eventually arose when the Germans provided their golfing prisoners with white coats to be worn when retrieving balls, reducing — if not completely erasing — fears of being shot during a round.

“Mindblowing — it’s crazy,” Nenno said, laughing. “You think that would deter them, but it didn’t.”

“When they say truth is stranger than fiction, I feel like this is one of those moments because it’s such a mix of interesting things. A sport being played in a place that’s sort of unfathomable to enjoy any sort of recreation, let alone something we see as needing a proper course, needing proper equipment … these men made do with very little in order to make their experience better.”

Players occasionally shot at their captors, however, with stray balls careening through the windows of a guard kitchen and an occupied toilet. Neither incident drew major repercussions, with the golfers simply asked to move their tees.

“The Germans viewed the prisoners’ passion toward this peculiar game with ambivalence,” wrote Strege, “but welcomed the fact that it kept them occupied doing something other than planning or attempting to execute an escape.”

Escape

About that.

Immortalized in a book and then a film of the same name, what became known as the “The Great Escape” wasn’t even the first breakout at Stalag Luft III. The first, staged in October 1943, saw POWs use a homemade, hollow gymnastics vaulting horse to shuttle prisoners and digging equipment to a tunnel site, with the horse used to cover the burrowing operation underneath.

When three prisoners made a successful escape, suspicious German eyes homed in on the golf course and its sprawling mounds and greens. The course was immediately destroyed, and then reconstructed weeks later after golfers convinced guards they had played no part in the escape.

More tournaments and even a gambling system emerged over the subsequent months before the events of March 24, 1944, when RAF Squadron Leader Roger Bushell’s year-long plan for a mass escape was realized.

Three tunnels — named “Tom,” “Dick,” and “Harry” — were dug under the camp, with the latter 111-meter-long shaft serving as the successful exit route for 76 prisoners. Yet only three POWs — two Norwegians and a Dutchman — made it back to allied territories. Of the remaining fugitives caught in the subsequent mass search operation, 50 were executed by firing squad under direct orders from an enraged Adolf Hitler.

Golf continued at Stalag Luft III, right up until January 1945, when the approaching Soviet army meant the remaining prisoners were forced on a freezing, brutal march to other POW camps.

Many would be liberated months later, including Ward-Thomas, who — having written golf match reports for the camp paper during his incarceration — returned to England determined to pursue a career in sports journalism.

He succeeded emphatically, enjoying a long career at The Guardian as one of Britain’s most esteemed golf writers, and publishing several books. In 1979, he donated two balls he made while in Stalag Luft III to the USGA Golf Museum, artifacts that headline its exhibit on golf during the Second World War.

“There’s this really direct tie between the man who’s telling his experience in real time and also to us generations later, and the objects in the museum,” Nenno said.

“This is just such a good example of people trying to make a dehumanizing experience more human and make it, in some way, aid their physical and mental health. Just to keep their heads on.”