CNN

—

Sean Elliott knows a lot about miracles.

He’s the basketball star behind the “Memorial Day Miracle,” arguably the most famous shot in San Antonio Spurs history. It was Memorial Day 1999, Game 2 of the Western Conference Finals.

The Spurs were playing the Portland Trail Blazers on their home court, the Alamodome, and they were down by two. With 12 seconds left on the clock, Elliott fired off a 3-point shot from the sideline. He was so close to the edge of the court, some of the commentators thought he might step out of bounds.

The crowd roared, Portland’s Amare Stoudemire looked stunned, and the Spurs eked out a 86-85 victory. They would go on to win the championship title that year – their first of five to date.

Elliott’s kidneys were failing when he made that shot, and to hear him tell it, only a few people knew at the time. He’d unexpectedly developed focal segmental glomerulosclerosis when he was 25. This disease prevents the kidneys from doing their job, that is filtering waste from the blood.

Elliott’s health issues became more public several weeks later when the 31-year-old, newly minted NBA champion, had to step away from his team. He took his talents and prayers to San Antonio Methodist Specialty and Transplant hospital to get a kidney transplant.

According to the NBA’s Chief Communications Officer Mike Bass, Elliott became the first active [NBA] player to return to play following a transplant.

“I see people all the time that have no idea about my story … and I’ll say, ‘Oh, yeah, I had a kidney transplant,’” Elliott, a two time NBA All Star who went on to play 11 seasons with the Spurs and one with the Detroit Pistons, told CNN Sport.

“And they have absolutely no idea,” added Elliott, who is now a TV Analyst for the Spurs. “And I think that was part of my original goal … just to kind of make people forget about it and treat me like a normal person.”

‘I had this jolt of energy’

The desire for normalcy is common among transplant recipients. Elliott says he started feeling abnormal years before his transplant – around the 1992-93 season. He said he felt lethargic, lost his appetite, and noticed his hands, feet and face start to swell. He didn’t know what was happening at first and was eventually diagnosed with a kidney disease.

Elliott kept playing, despite declines in his health and performance, until he couldn’t push it to the side any longer. His kidney function was so poor, he had two choices – dialysis or transplant. The former would have meant the end of his NBA career, so he chose the latter.

According to Elliott, the transplant changed everything.

“I say it’s like flipping on a light switch … all of a sudden, I had this jolt of energy … I was clear headed. I could do things. I felt normal again. I didn’t know what normal felt like for such a long time,” he explained.

At 55, Elliott’s “normal” now involves watching his kids grow up and fulfilling a promise to his mother to earn a college degree. He graduated from the University of Arizona this May, nearly 35 years after he first enrolled and then left once he was drafted by the San Antonio Spurs in 1989.

He said he also plays golf, exercises regularly and eats a healthy diet. The kidneys don’t process all proteins well, so he said he eats chicken and fish, and very few porterhouse steaks. And of course, a lot of vegetables.

“I always joke to my wife [and]my friends that I’m so vain. I don’t want to get out of shape or overweight. But the real reason is I just want to know, I want to challenge my body every day and I want to keep myself in good physical condition,” he said.

Elliott’s name is but one of a short list of former professional athletes who have received transplants. The list includes former British/Canadian soccer player Simon Keith, who received a heart transplant in 1986; Olympic medalist and snowboarder Chris Klug, who got a liver transplant in 2000; and Alonzo Mourning, an NBA star who received a kidney transplant in 2003.

Elliott said he regularly speaks with people who are preparing to get kidney transplants about what they can expect – he spoke to Mourning as well as comedian George Lopez, also a transplant recipient.

The first successful long-term kidney transplant was performed in 1954. Since then, over a half a million people have received kidney transplants in the US, which tend to function, on average, 12 to 20 years after the procedure.

Raising awareness about kidney disease and encouraging people to monitor their kidney health is another way Elliott likes to pay it forward.

Data from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases show that nearly 800,000 Americans have end stage kidney disease or kidney failure – which means your kidneys no longer function well enough to meet your body’s needs. It’s the most common reason people get kidney transplants.

African Americans are three times more likely to need a kidney transplant than their non-Hispanic White counterparts, according to a NIH study from 2019.

‘Beginning of a new life’

Elliott calls kidney disease a silent killer, especially among African Americans, like himself. This is because people don’t typically experience symptoms until the disease is at an advanced stage. Additionally, getting access to quality medical care can also be a challenge for some Black Americans, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Elliott, who was blindsided by his kidney disease, said he had access to top-notch care. Since his surgery, he has worked with the National Kidney Foundation and the U.S. Transplant Games (now called the Transplant Games of America), to let people know what’s possible after transplant.

“I just felt incredible to go out to the Transplant Games, be honored there, to be present. We ran a couple of basketball camps, interacted with a lot of the athletes, and they could see that, you know, look at this guy. He’s not on his deathbed; that, an organ transplant is the beginning of a new life. It’s not the end of you,” he said.

He has never competed in the American or World Transplant Games, but said meeting other transplant athletes gave him perspective on his own transplant experience.

“There were lots of cases where family members didn’t step up for people that needed a transplant and even friends didn’t step up. And so for me, I just consider myself very fortunate because my story doesn’t happen all the time,” he said.

He’s right: an estimated 17 patients die per day waiting for an organ transplant, according to the Health Resources & Services Administration.

Elliott’s story is indeed a fortunate one. Once he told his family that he needed a kidney, his parents and siblings got tested to see if they could help. His older brother Noel ended up being the best match. When they learned that, Noel “did not hesitate for a second. He stepped up and the rest is history,” recalled Elliott.

The brothers are still close today.

“Our relationship is still the same. And we were close as kids. I mean, my brother was the one who was shagging balls for me all the time. He was the one who was passing me ball after ball when I was first trying to dunk.”

Modern day Miracle

The game-winning shot behind “Memorial Day Miracle,” has a well-deserved place in NBA history, but Elliott’s post-transplant play is every bit as miraculous.

Immunosuppressants, especially at the high dose most transplant patients have to take for about a year after surgery, can affect muscle mass, weight, and make the body susceptible to infection and illness.

When Elliott returned to the NBA just seven months after surgery, he received a standing ovation and went on to start in 19 games during the 1999-2000 season and then played 64 games in the next (52 regular season games and 12 playoff games).

Elliott says being the NBA’s first active transplant player meant he had to “jump through a lot of loopholes and sign a lot of waivers.”

He says his health, playing time and performance were closely monitored.

“I was okay with that … I was just thrilled that I was going to be able to actually get out there and play after a transplant. I mean, a lot of people at the time were like, ‘Are you crazy? Why don’t you just hang them up or just go ahead and ride off into the sunset?’ But I wasn’t ready for that,” he said.

Although he said he often felt strong and met performance goals, Elliott suffered a rotator cuff injury and wasn’t able to take non-steroidal anti-inflammatories for pain because he didn’t want to tax his new kidney. He said he could only ice himself. This proved to be a sticking point.

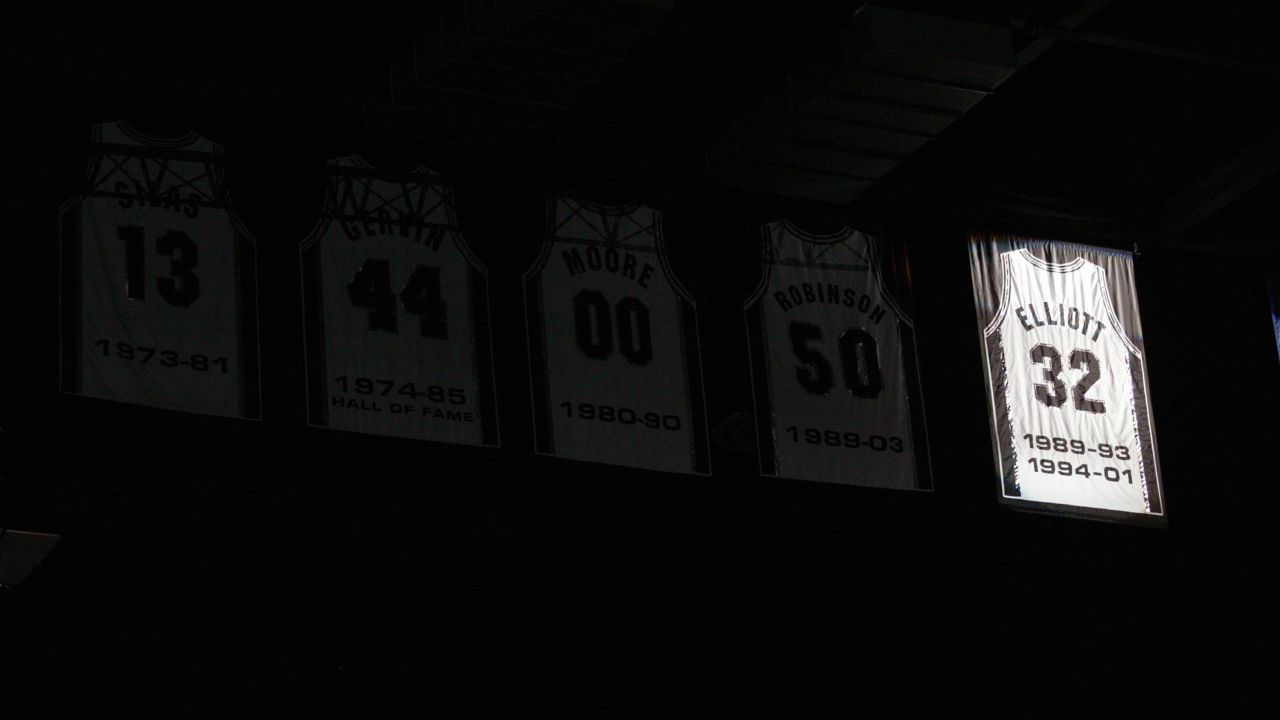

By the end of the 2000-01 season, he said his body was hurting every day and he’d had enough. He retired that year, at the age of 33. A few years later, his jersey, No. 32, was retired as well.

Since then, Elliott has stayed close to the Spurs franchise and gets to talk regularly about the state of play in the league. His kidneys and his health are in good shape.

Transplanted organs have no “expiration date” – no guarantee about how long or how well they’ll work. They save lives but sometimes they lead to secondary problems like infections, illness or organ rejection. Elliott said he’s found peace with the unpredictable by staying present and focusing on what he can control, not what he can’t predict.

“I lost my mother in ’14, lost my dad in ‘15. And I heard somebody tell me one day, no one gets out of here alive. And you know, that’s the truth,” he began.

“I don’t live fearful of what could happen in the future. I try to focus on right now and be mindful of the present. And I think that’s the biggest thing that helps me. I’m just going to do the best I can. I’m still as healthy as I can [be],” he said. “And then whatever happens, happens … And so, control what you can and enjoy every single day.”