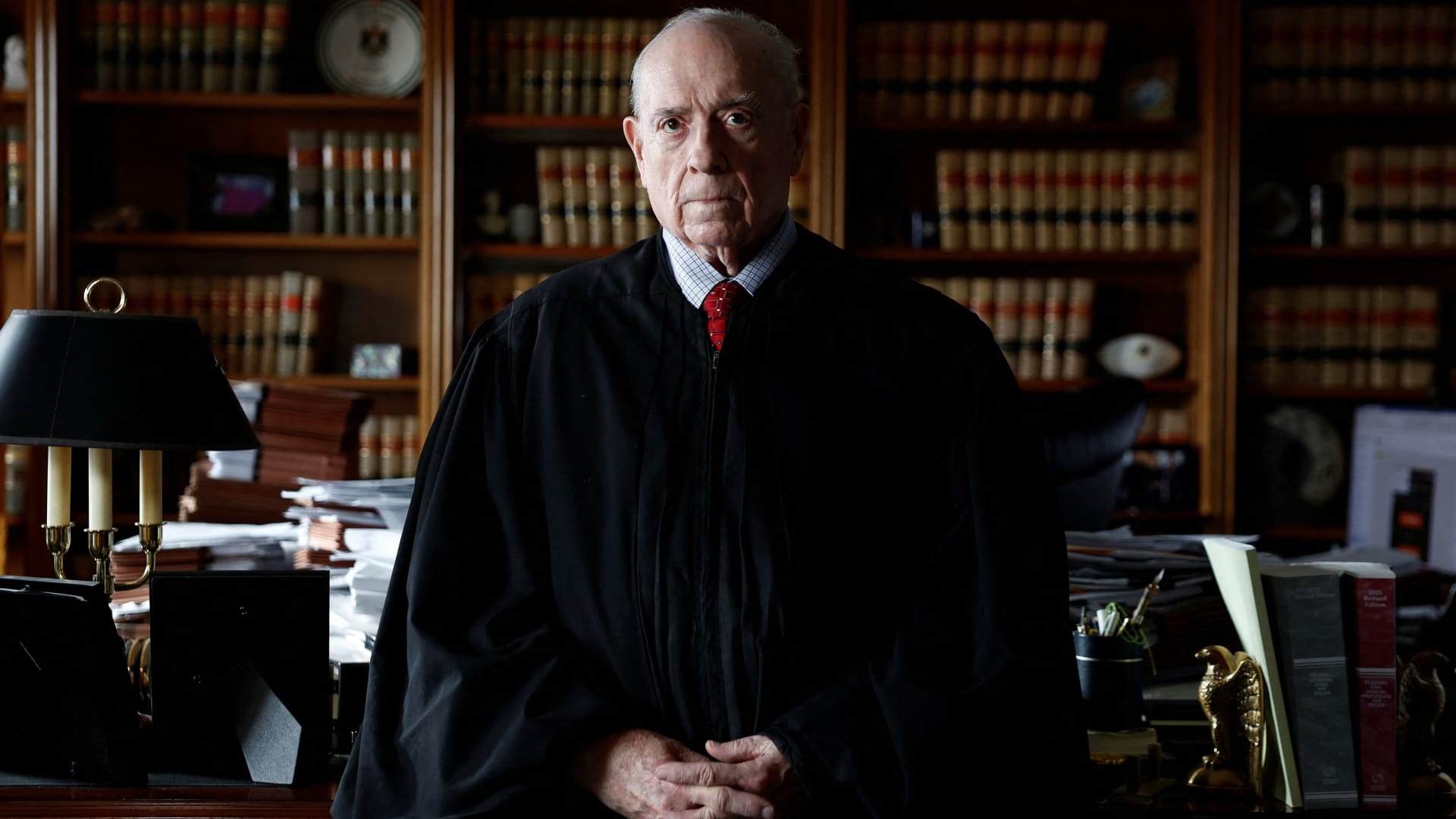

U.S.District Judge Royce Lamberth has been threatened by angry criminals. Drug cartels. Even al Qaeda.

But nothing, Lamberth says, prepared him for the wave of harassment after he began hearing cases against supporters of former President Donald Trump who attacked the U.S. Capitol in a bid to overturn the 2020 election.

Right-wing websites painted Lamberth, appointed to the bench by Republican President Ronald Reagan, as part of a “deep state” conspiracy to destroy Trump and his followers. Calls for his execution cropped up on Trump-friendly websites. “Traitors get ropes,” one wrote. After he issued a prison sentence to a 69-year-old Idaho woman who pleaded guilty to joining the Jan. 6, 2021, riot, his chambers’ voicemail filled with death threats. One man found Lamberth’s home phone number and called repeatedly with graphic vows to murder him.

“I could not believe how many death threats I got,” Lamberth told Reuters, revealing the calls to his home for the first time.

As Trump faces a welter of indictments and lawsuits ahead of this year’s election, his loyalists have been waging a campaign of threats and intimidation at judges, prosecutors and other court officials, according to a Reuters review of threat data compiled by the U.S. Marshals Service, posts on right-wing message boards, and interviews with more than two dozen law-enforcement agents, judicial officials and legal experts.

As the frontrunner for the 2024 Republican presidential nomination – and a defendant in four criminal cases alleging 91 felonies – Trump has fused the roles of candidate and defendant. He attacks judges as political foes, demonizes prosecutors and casts the judicial system as biased against him and his supporters.

These broadsides frequently trigger surges in threats against the judges, prosecutors and other court officials he targets, Reuters found. Since Trump launched his first presidential campaign in June 2015, the average number of threats and hostile communications directed at judges, federal prosecutors, judicial staff and court buildings has more than tripled, according to the Reuters review of data from the Marshals Service, which is responsible for protecting federal court personnel.

The annual average rose from 1,180 incidents in the decade prior to Trump’s campaign to 3,810 in the seven years after he declared his candidacy and began his practice of criticizing judges. In all, the Marshals documented nearly 27,000 threatening and harassing communications targeting federal courts from the fall of 2015 through the fall of 2022, a volume they consider unprecedented in their 234-year history. There is no national data collection for threats against state and local judges. Many states do not even track the problem.

Since late 2020, Trump has ramped up his criticism of the judiciary dramatically, first amid his dozens of failed lawsuits seeking to overturn his election loss and, more recently, amid a cascade of criminal and civil litigation. In that time, serious threats against federal judges alone have more than doubled, from 220 in 2020 to 457 in 2023, as Reuters reported on Feb. 13.

“Donald Trump set the stage,” retired Ohio Supreme Court Chief Justice Maureen O’Connor, a Republican who stepped down at the end of 2022, said in an interview. Trump “gave permission by his actions and words for others to come forward and talk about judges in terms not just criticizing their decisions, but disparaging them and the entire judiciary.”

Trump and his spokespeople did not respond to requests for comment. He has appeared defiant in public comments on the judiciary, saying in January that if the criminal cases against him hurt his election prospects, “it’ll be bedlam in the country.”

Despite the rise in threats, arrests are rare. The U.S. Justice Department says it does not track the number of people charged or convicted for threatening judges. Reuters identified just 57 federal prosecutions for threats to judges since 2020 in a review of court databases, Justice Department records and news accounts.

Whether to press federal charges is typically up to the Justice Department and its prosecutors based on evidence gathered by the Federal Bureau of Investigation. The Justice Department declined to comment on judicial threats and prosecutions. The FBI and Marshals would not comment on specific incidents. Marshals Director Ronald Davis told Reuters that the agency is dedicating unprecedented resources to judicial protection. The FBI said it “takes all potential threats seriously.”

In the case of Lamberth, the federal judge in Washington, D.C., U.S. Marshals found the culprit, who has not been identified, and warned the man to stop. No arrest was made. The Marshals upgraded Lamberth’s home security system. The calls stopped, but his concerns lingered about threats that now come from “ordinary people you wouldn’t suspect,” Lamberth said.

For judges, threats have always been part of the job. But traditionally they have come from aggrieved parties – a criminal angered by a long sentence, a spouse by a divorce ruling, a businessman by a bankruptcy decision. Today, a single politically charged case can generate hundreds of threats from people with no direct interest in the matter.

Those cases can generate rage across the political spectrum.

The U.S. Supreme Court’s 2022 decision to end the legal right to abortion stoked left-wing anger against the court’s conservatives, including an alleged assassination attempt against Justice Brett Kavanaugh. After a draft of the ruling leaked, police arrested Nicholas John Roske outside Kavanaugh’s home, armed with a gun, a knife and tactical gear. He said he was enraged by the draft ruling and planned to kill the justice. He has pleaded not guilty to attempted murder and awaits trial.

Many of the threats against judges examined by Reuters echo Trump’s statements in social media posts and speeches, where he has attacked judges as “totally biased,” “crooked,” “partisan” and “hostile,” dismissed courts as “rigged” and called prosecutors “corrupt.” Threatening messages on pro-Trump online forums often repeat those terms or cast the former president as a heroic figure besieged by corrupt judges in secret “Democrat” plots.

“Hanging judges for treason is soon to be on the menu boys!” said one anonymous January post on the pro-Trump forum Patriots.Win. The post referred to federal judge Lewis Kaplan, who presided over writer E. Jean Carroll’s successful defamation suit against Trump in New York. Kaplan did not respond to a request to comment.

Judges at every level of the U.S. legal system have voiced alarm, saying the rising tide of threats jeopardizes the judicial independence that underpins America’s democratic constitutional order. Judges not only rule on criminal and civil cases, but also act as a check on the power of the U.S. president, Congress and state governments.

Trump has bristled at the rule of law. In 2022, he called for the “termination” of the U.S. Constitution if it would restore him to power. In December, he said he wanted to “be a dictator for one day,” his first back in office, so he can wall off the U.S.-Mexico border.

Reuters interviewed 14 sitting judges and four retired judges. Some were reluctant to share details about threats they’ve received or the security precautions they’ve taken. But all expressed worry about the growing volume of threats and their potential to undermine courts’ legitimacy.

“We can’t have a situation where judges are in fear that a ruling, an unpopular ruling, can lead to reprisals,” U.S. Court of Appeals Judge Richard Sullivan, who chairs a federal judiciary committee that oversees security for court personnel, said in an interview.

Trump has derided the judiciary in intensely personal terms since his 2016 presidential campaign. Back then, he repeatedly attacked a federal judge handling a fraud lawsuit against the defunct Trump University. He accused Indiana-born Gonzalo Curiel of bias based on his Mexican heritage, called him a “hater” with a conflict of interest because of Trump’s hard-line immigration policies, and suggested investigating him. “They ought to look into Judge Curiel, because what Judge Curiel is doing is a total disgrace.” Curiel declined to comment.

The berating of Curiel established the tone for Trump’s subsequent attacks on the judiciary, which set him apart from other contemporary political figures.

In 2017, Trump excoriated federal Judge James Robart, a Republican appointee who blocked an executive order barring travelers from certain predominantly Muslim nations from entering the United States. Trump urged people to blame the “so-called judge” for opening a door to potential terrorists. Robart told Reuters he received thousands of hostile messages, including more than 100 threats serious enough to trigger Marshals Service investigations. He was not aware of any arrests related to the threats.

When Trump’s term ended, the threats continued as courts rejected dozens of lawsuits alleging electoral fraud filed by Trump and his allies.

Whenever a case against Trump was in court, “we would see a noticeable uptick in threats directed at whatever judge had the case,” said Jon Trainum, who headed the U.S. Marshals’ unit that investigated judicial threats for five years before retiring in 2021.

More recently, Trump has blasted judges and prosecutors involved in the multiple civil and criminal cases against him. He has described his jailed supporters from the Jan. 6 Capitol riot as patriots and political prisoners. And he has lashed out at state judges who have ruled that he should be disqualified from the 2024 presidential ballot based on the criminal charges he faces.

In all, at least 10 judges and four prosecutors have received threats and harassment, according to interviews with court officials and a review of police records, federal court files, social media and news reports.

In a Feb. 26 court filing, Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg blamed Trump’s “inflammatory remarks” for a series of death threats he received while prosecuting a case alleging Trump paid hush money to cover up an affair with a porn star. One letter contained white powder and a note: “Alvin: I am going to kill you.” Another warned he would “get assassinated” if he didn’t “leave Trump alone.” Citing a surge in threats to 89 in 2023 from one the year before, Bragg sought a judge’s order to limit Trump’s public statements.

Another frequent Trump target is New York Justice Arthur Engoron, who ordered the ex-president this month to pay $454 million in penalties for fraudulently overstating his net worth to dupe lenders to his real-estate business. A security officer in Engoron’s court testified in a November filing that the judge and his staff had received “hundreds of threats, disparaging and harassing comments and antisemitic messages” linked to the case. “Trust me when I say this. I will come for you,” one message promised. “Trump owns you,” another warned. No one has been arrested.

Tanya Chutkan, a federal judge in Washington assigned to Special Counsel Jack Smith’s criminal election-subversion case against Trump, also has been targeted. On Trump’s social media platform, Truth Social, the ex-president has called her a “biased, Trump-hating judge” incapable of giving him a fair trial.

On Aug. 4, the day after Trump was formally charged in the case, Trump posted on Truth Social: “If you go after me, I’m coming after you!” The next day, Chutkan, who is Black, received an alarming voicemail. “You stupid slave n—” a woman’s voice said, using a racist slur, according to an affidavit filed by prosecutors in court. “If Trump doesn’t get elected in 2024, we are coming to kill you. So tread lightly, bitch.”

Chutkan’s office declined a request for comment from the judge.

A Trump spokesperson said at the time that his social media comments were “the definition of political speech” and targeted interest groups, not judges. But Special Counsel Smith highlighted Trump’s post in a Sept. 15 court motion. Trump was trying “to undermine confidence in the criminal justice system” through “inflammatory attacks” on those involved in the case, he said.

Federal agents arrested the woman who threatened Chutkan, Abigail Jo Shry, 43, of Texas. She pleaded not guilty to a federal felony of threatening a judge and is awaiting trial. Her lawyer declined to comment.

Shry’s case is unusual. Few people face charges for threatening judges and the federal courts, according to a Reuters analysis of legal databases and other public records.

Over the last four years, the Marshals investigated more than 1,200 threats against federal judges that they considered serious, according to the data provided to Reuters. Among the 57 federal prosecutions Reuters identified during that period, 47 involved threats against federal judges, six involved threats against state judges, and four involved threats against both. There is no national data on state-level prosecutions for threats against judges.

Judges tell of the shock of suddenly being besieged with threats, and some express frustration that most of their harassers remain unpunished.

In March 2017, after a federal court in Hawaii blocked Trump’s second attempt to ban travelers from some Muslim countries, Trump said to applause at a Tennessee rally that the decision was “political.” Within 24 hours, at least one website published the home address of the presiding judge in that case, Derrick Watson. Demands to execute Watson and his fellow judges appeared online. “We need to start hanging these traitors,” one person wrote on a right-wing website. Thousands of angry calls poured into Watson’s office, the judge told Reuters in his first interview on the experience.

Marshals deemed dozens of the messages serious death threats and assigned Watson a 24-hour security detail for nearly a month, he said. His family traveled for over a week in an armed three-car convoy for daily routines, including grocery shopping and picking up his sons from school.

“When those threats involve our family, it’s on another level,” he said.

Marshals questioned a New Jersey man and an Arizona woman who had made particularly alarming threats, warning them of potential charges if they didn’t stop, Watson said. No one was arrested, he said, but the worst threats stopped. Since then, he remains a target on Patriots.Win, the pro-Trump message board. “Dox this judge, go to his house,” said one post last year that remains on the site.

Patriots.Win did not respond to a request for comment.

Watson said he worries that the climate of intimidation will deter people from serving on the bench. Without better enforcement of existing laws and the passage of new ones to safeguard judges, would-be jurists “will be chilled by their concerns over physical safety,” he said.

In Washington D.C., federal Judge Reggie Walton says he received one or two threats in his first 18 years on the bench, handling major criminal cases. But since Walton, who is Black, began hearing cases against Jan. 6 Capitol attackers, people enraged by the prosecutions routinely leave threatening and racist messages on his office phone, including one chilling threat targeting his family.

“An individual from Texas called and left two messages – the first one threatening me personally, and the second one making a threat against my daughter,” Walton told Reuters. The caller knew his daughter’s name, and his address. “That was very disconcerting,” he said. “I surely would not want something to happen to a family member.”

Walton said he turned the calls over to the Marshals Service, which contacted the FBI. Federal agents visited the man in Texas, Walton said, but decided not to file charges. “They were of the view that he was apologetic and contrite about what he had done,” he said. The incident has not been previously reported. Walton said he was disturbed by the decision not to arrest the man but felt it “should be independently made,” without pressure from him.

Threats against judges can be prosecuted under multiple federal statutes, some punishable by up to 10 years in prison and a maximum $250,000 fine. But many menacing messages don’t meet the standard for a criminal offense – generally defined as a direct threat that puts a person in fear of death or violence – because of the U.S. Constitution’s sweeping free-speech protections. Drawing the line can be difficult, say former Marshals and judges. Federal agents often look for language reflecting a clear intent to act, rather than simply suggesting a frightening outcome.

“If somebody says, ‘Judge, you should be hung from a gallows in front of the courthouse,’ that’s different than, ‘Judge, I am coming to your courthouse and I’m going to hang you’,” said Carl Caulk, a former assistant director of the Marshals Service who retired in 2015.

The most serious threats lead to criminal investigations, typically by the FBI. Agents sometimes warn threateners of prosecution if they do it again, rather than arrest them, according to judges and prosecutors. But the volume of emails, phone calls, social media posts and other communications that contain threatening language is so enormous that law enforcement has struggled to keep up, judges and prosecutors say.

“It’s like drinking through a fire hose, and you know we only have so much bandwidth,” said Trainum, the former senior Marshals official. “We have to go through all of the ones that we receive and triage them to some degree. All of that takes time. All of that takes resources. All of that takes personnel.”

State judges also face politically inspired threats.

Arizona’s Maricopa County, an epicenter of unfounded election conspiracy theories, logged more than 400 cases of threats and harassment targeting judges, their staff and the courts between 2020 and 2023, according to previously unpublished county data reviewed by Reuters. Maricopa officials didn’t track threats until noticing a spike in 2020, a county official said.

In Wisconsin, a presidential battleground state, lawmakers are considering stronger protections for judges following 142 threats made against state judges in the last year, according to data from the Wisconsin Supreme Court Marshal’s Office.

In Colorado, after the state’s seven supreme court justices ruled in December to disqualify Trump from the state’s 2024 presidential ballot, the ex-president blasted the court in speeches and social media posts. The judges faced multiple incidents of threats and harassment, including four “swatting” attempts, or hoax calls intended to draw police to their homes, said the Denver Police Department. The department tightened security for the justices. No one has been arrested, a police spokesperson said.

While there is no national data on intimidation of state judges, serious threats against them are growing, according to a survey of 398 mostly state judges, completed in 2022, by the National Judicial College, a judicial education group. Nearly 90% expressed some worry over their safety, and one in three reported carrying a gun at some point for protection, the previously unreported survey found.

Despite the torrent of threats, physical attacks against judges remain relatively rare. Since 2000, at least three state judges and one federal judge have been killed in connection with their work.

But the 2020 killing of the son of New Jersey federal Judge Esther Salas highlighted the risks. The shooter, a self-described “anti-feminist” lawyer, blamed Salas for moving too slowly on a case he was involved in. He dressed as a postal delivery driver, shot her 20-year-old son when he opened the door, and wounded her husband. The shooter later killed himself.

Following her son’s murder, Salas campaigned for new laws to better shield judges’ personal information in public records, and prevent them from being revealed by internet data brokers. In 2022, Congress passed a federal version, named for Salas’ son, Daniel Anderl. New Jersey also passed a strong version of that law, Salas said, but most other states have not. “We need to make sure that judges are safe and are able to do their jobs without feeling like targets in target practice,” she said in an interview.

The Salas case “was a wake-up call for the entire country,” said Davis, the Marshals Director.

An earlier killing offered a powerful lesson for Lamberth, the judge whose sentences for Jan. 6 Capitol rioters have drawn death threats. Seven months after he took the bench in 1987, his close friend Richard Daronco, a federal judge in New York, was murdered at home by the enraged father of a woman whose sexual discrimination suit was dismissed in Daronco’s court.

“We had never even contemplated that one of us could get killed in this job,” Lamberth said.

Soon after, Lamberth, a Vietnam War veteran, received his first death threat. A letter to his chambers said he would be murdered if he did not free a drug dealer he had jailed. Marshals had briefed his family on security precautions, but they were nervous, Lamberth said. “We had to adjust to the fact we could be a target.”

Another scare came after al Qaeda’s September 2001 attacks. The U.S. government feared that Lamberth, then chief judge on the U.S. Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, might be an assassination target because he had authorized the first wiretaps on the Islamist militant group in the 1990s.

“I went everywhere with Marshals protection for a couple of years,” he said.

Still, Lamberth said, he was unprepared for the sheer volume of threats he’s received in connection to the Jan. 6 riot cases. Many are from people on the right enraged by the sentences he’s issued, but he has also received some threats from the left. While many of them are idle, Lamberth said, the Marshals have left the judge with little doubt that some are “dangerous,” and he and his family remain on constant alert.

Whenever he receives a delivery at home, he remembers what happened to Judge Salas’ family in New Jersey.

“Living this way, it does change your life,” he said.