The weather was so cold, the frozen pitch so hard, that Viv Anderson doubts the match would be played today.

Indeed, the stubborn frost – as firm as concrete in some corners of the pitch – prompted England’s players to wear rubber-soled cleats, rather than metal studs, for parts of the game. Yet despite the atrocious conditions, the fixture went ahead as planned, and after 90 minutes of less-than-inspiring football, England had beaten Czechoslovakia 1-0 at Wembley Stadium.

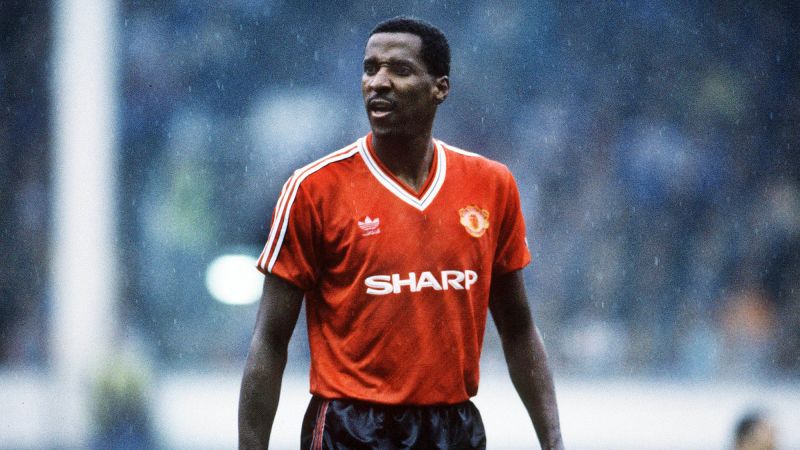

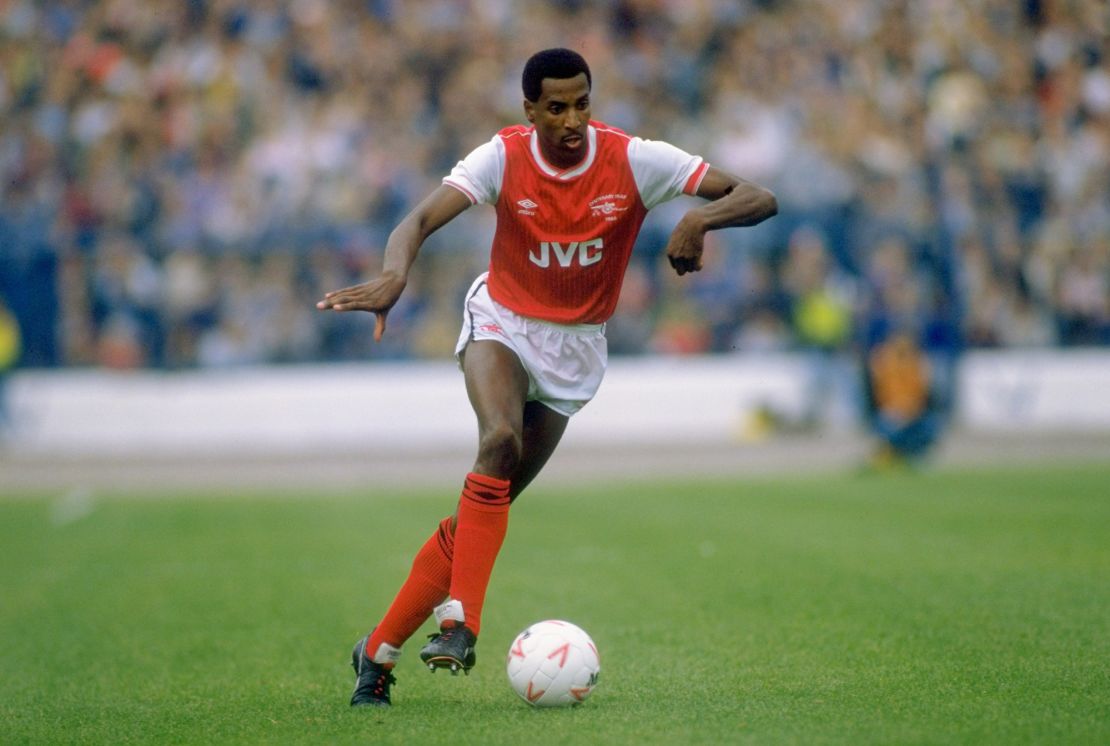

More importantly, however, was the fact that Anderson had made history as the first Black player to represent the England national team. This was more than 40 years ago, but even today, it is an accolade that the former Nottingham Forest, Manchester United and Arsenal defender carries with pride.

“It was a massive thing at the time,” Anderson tells CNN Sport. “I’m very privileged and pleased to be first; to be first at anything is a great achievement, I think.”

Days before he stepped onto the pitch at Wembley, journalists had already begun interviewing Anderson’s parents, teachers and childhood coaches, eagerly anticipating the then-22-year-old’s landmark England appearance.

Black players had previously represented England at youth level, but Anderson, whose parents left Jamaica as part of the Windrush generation, was the first to make an appearance for the senior team. He even received telegrams from Queen Elizabeth II and Elton John to mark the occasion.

But for a young player winning the first of 30 England caps, it was important to shut out the fanfare around his historic debut. “You go into football mode – what you used to do every Saturday afternoon,” Anderson recalls. “I went at the first header, the first tackle, first pass and made sure I got it right and didn’t miss out on any of those things.”

Now is an appropriate time for Anderson to be reflecting on his playing days having recently decided to sell a collection of items from his career – medals, trophies, England caps, and the jersey he wore for his international debut in 1978.

He initially hoped that the jersey sale would be a way to financially support his family – “my son’s getting married next year, and it was a good reason to auction it off,” Anderson explains – before he started to unearth other memorabilia buried away in a garage.

“We rummaged through and we found a whole heap of things that had never been out in the daylight for about 40 years,” he says.

The jersey, on sale with Graham Budd Auctions last week, remains in Anderson’s possession after failing to reach its reserve price of around $40,000 (£30,000), but the whole collection reached a hammer price of roughly $180,000 (£135,335).

The haul of memorabilia is testament to Anderson’s glittering career, during which he won back-to-back European Cup titles, as well as the First Division – the old name for the top-flight of English football – with Nottingham Forest and the FA Cup and Football League Cup with Manchester United and Arsenal.

But not all of his memories are happy ones. Up and down the country, Anderson says that racist abuse formed an ugly backdrop to some of his football career. He remembers one instance when fruit was thrown at him from the stands – apples, pears, and bananas – as he tried to warm up; on a separate occasion, a glass bottle was hurled his way.

It was Brian Clough, the late Forest manager, who encouraged him to persevere despite the abuse – even making him laugh in the face of it. On the day that Anderson was pelted with fruit in Carlisle, Clough told him to “get back out there and get me two pears and a banana.

“It was funny at the time, and everybody laughed, but afterwards, he pulled me to one side and said, ‘Listen, if you’re going to let people dictate to you in this stadium like today, you have to sit down as quick as you can, you’re no good to me,’” recalls Anderson.

“‘You’ve got to go out there and prove to them that you can play. We believe in you, you’ve got to prove it, and that’s by doing the things I say and not reacting to what people might say or what people might throw at you.’ It was a good learning curve for a 17-year-old, and I took that on board throughout my career.”

Anderson wasn’t the sole target of abuse. Racism was widespread on the football terraces in England during the 1970s and 80s when players like Clyde Best, Laurie Cunningham, Brendon Batson and Cyrille Regis were starring in the First Division.

“The worst for me was getting my first England cap and receiving a bullet through the post, saying, ‘If you put your foot on our Wembley turf, you’ll get one of these through your knees,’” Regis, who played as a forward for West Brom and Coventry, told CNN Sport in 2017.

“But over the years, you learn how to turn a negative into a positive. You say, ‘Right, you’re not going to stop me doing what I want. I’m going to turn that into motivation and go out there and prove you wrong, just do the best I can.’”

Anderson developed a similar attitude, always determined to forge a successful career irrespective of the reception that he received from supporters.

“It’s one of those things we (Black players) all had to get through if we wanted to make a career,” he says. “Because remember, first and foremost, I wanted to be a footballer, and whatever it took I did to achieve that goal.

“From a really early age, I was always kicking a football. Whether it be on the playground, whether it be at home with nieces and nephews, I was always playing football. My goal was always to be a footballer, by hook or by crook, so to achieve that was an unbelievable feat.”

An industrious tackler who played with pace and power, Anderson was one of the standout full-backs of his generation. His long legs and ability to rob opponents of the ball earned him the nickname “Spider,” and he became a mainstay of the English game before his retirement in 1995.

He says that the sport has “still got a lot to learn” when it comes to diversity and tolerance. Racism persists in the stands and on social media, and Anderson is also struck by how few Black managers there are at the top of the English game.

He remembers a newspaper headline proclaiming the start of a new revolution for Black managers when his friend, Keith Alexander, was appointed by Lincoln in 1993, but “20 odd years on, maybe longer, 30 odd years on, nothing’s changed,” says Anderson.

That’s despite the English Premier League attracting players from all over the globe, with 68 different nationalities represented on the pitch last season.

“There is something fundamentally wrong with the recruitment … There’s a big gulf between playing and managing and the higher level, the administration side,” says Anderson. “I don’t know what the answer is.”

The 2023 Szymanski Report, commissioned by the Black Footballers Partnership (BFP), found that only 14% of coaches with the highest coaching qualifications in England were Black, while only 4.4% of management positions across England’s top four leagues were occupied by Black people.

“We have made great strides to help increase the number of individuals from underrepresented groups within the coaching pathway, and we continue to make strong progress in this area,” the English Football Association said in a statement to CNN Sport.

It added: “We continue to work hard to influence the talent pipeline of future coaches through the grassroots game, however we are not part of the recruitment process for professional clubs, so this is not something we can solve alone.

“All organisations, leagues and clubs across English football have an important role to play, and only by continuing to work together can we make our game truly inclusive.”

Premier League CEO Richard Masters, meanwhile, said last year that the league “will continue to progress” its existing coach inclusion programmes, as well as “working on new programmes to ensure even more opportunities are available for people from ethnically diverse backgrounds.”

As for Anderson, his name is often mentioned alongside other Black footballing pioneers, those who came before and after him. That includes former Plymouth Argyle striker Jack Leslie, picked to represent England in 1925 but then denied the chance to play internationally because he was Black.

Former FA Chairman Greg Clarke has called Leslie’s story “incredibly sad,” adding that football is “in a very different place today.”

It means that Anderson, now 68, is the person who officially paved the way for future generations of Black players representing England. Though his debut was, in his own words, “not a great game” played on a “terrible pitch,” it’s still an experience he holds dear.

“It ranks right up there,” says Anderson. “To play for your country – to put the shirt on and to walk out to 100,000 people … It’s a great feeling.”