The U.S. stock market has become dominated by about a handful of companies in recent years. Some experts question whether that “concentrated” market puts investors at risk, though others think such fears are likely overblown.

Let’s look at the S&P 500, the most popular benchmark for U.S. stocks, as an illustration of the dynamics at play.

The top 10 stocks in the S&P 500, the largest by market capitalization, accounted for 27% of the index at the end of 2023, nearly double the 14% share a decade earlier, according to a recent Morgan Stanley analysis.

In other words, for every $100 invested in the index, about $27 was funneled to the stocks of just 10 companies, up from $14 a decade ago.

That rate of increase in concentration is the most rapid since 1950, according to Morgan Stanley.

It has increased more in 2024: The top 10 stocks accounted for 37% of the index as of June 24, according to FactSet data.

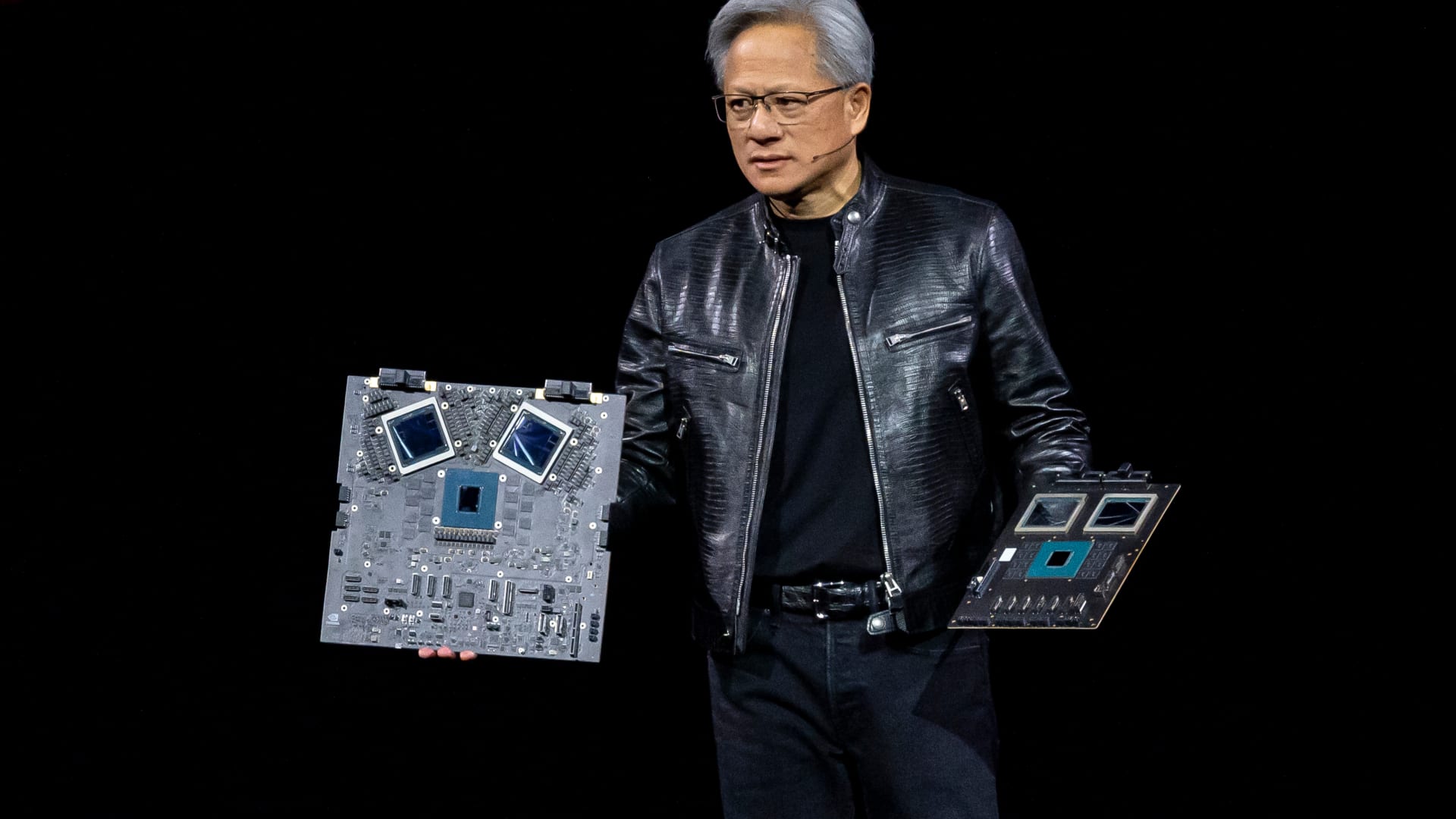

The so-called “Magnificent Seven” — Apple, Amazon, Alphabet, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia and Tesla — make up about 31% of the index, it said.

Some experts fear the largest U.S. companies are having an outsized influence on investors’ portfolios.

For example, the Magnificent Seven stocks accounted for more than half the S&P 500’s gain in 2023, according to Morgan Stanley.

Just as those stocks helped push up overall returns, a downturn in one or many of them could put a lot of investor money in jeopardy, some said. For example, Nvidia shed more than $500 billion in market value after a recent three-day sell-off in June, dragging down the S&P 500 into a multiday losing streak. (The stock has since recovered a bit.)

The S&P 500’s concentration “is a bit riskier than people realize,” said Charlie Fitzgerald III, a certified financial planner based in Orlando, Florida.

“Nearly a third of [the S&P 500] is sitting in seven stocks,” he said. “You’re not diversifying when you’re concentrating like this.”

The S&P 500 tracks stock prices of the 500 largest publicly traded companies. It does so by market capitalization: The larger a firm’s stock valuation, the larger its weighting in the index.

Tech-stock euphoria has helped drive higher concentration at the top, particularly among the Magnificent Seven.

Collectively, Magnificent Seven stocks are up about 57% in the past year, as of market close on June 27 — more than double the 25% return of the whole S&P 500. Chip maker Nvidia’s stock alone has tripled in that time.

More from Personal Finance:

Americans struggle to shake off a ‘vibecession’

Retirement ‘super savers’ have the biggest 401(k) balances

Households have seen their buying power grow

Despite the sharp increase in stock concentration, some market experts believe the concern may be overblown.

For one, many investors are diversified beyond the U.S. stock market.

It’s “rare” for 401(k) investors to own just a U.S. stock fund, for example, according to a recent analysis by John Rekenthaler, vice president of research at Morningstar.

Many invest in target-date funds.

A Vanguard TDF for near-retirees has a roughly 8% weighting to the Magnificent Seven, while one for younger investors who aim to retire in about three decades has a 13.5% weighting, Rekenthaler wrote in May.

Additionally, the current concentration isn’t unprecedented by historical or global standards, according to the Morgan Stanley analysis.

Research by finance professors Elroy Dimson, Paul Marsh and Mike Staunton shows that the top 10 stocks made up about 30% of the U.S. stock market in the 1930s and early 1960s, and about 38% in 1900.

The stock market was as concentrated (or more) around the late 1950s and early ’60s, for example, a period when “stocks did just fine,” said Rekenthaler, whose research examines markets since 1958.

“We’ve been here before,” he said. “And when we were here before, it wasn’t particularly bad news.”

When there were big market crashes, they generally don’t appear to have been associated with stock concentration, he added.

When compared with the world’s dozen largest stock markets, the U.S. market was the fourth-most-diversified at the end of 2023 — better than that of Switzerland, France, Australia, Germany, South Korea, the United Kingdom, Taiwan and Canada, Morgan Stanley said.

Big U.S. companies also generally seem to have the profits to back up their current lofty valuations, unlike during the peak of the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s and early 2000s, experts said.

Present-day market leaders “generally have higher profit margins and returns on equity” than those in 2000, according to a recent Goldman Sachs Research report.

The Magnificent Seven “are not pie-in-the-sky” companies: They’re generating “tremendous” revenue for investors, said Fitzgerald, principal and founding member of Moisand Fitzgerald Tamayo.

“How much more gain can be made is the question,” he added.

Concentration would be a problem for investors if the largest companies had related businesses that could be negatively impacted simultaneously, at which point their stocks might fall in tandem, Rekenthaler said.

“I’m having trouble envisioning what would hurt Microsoft, Apple and Nvidia at the same time,” he said. “They’re in different aspects of the tech marketplace.”

“In fairness, sometimes you can be surprised: ‘I didn’t see that type of danger coming,'” he added.

A well-diversified equity portfolio will include the stock of large companies, such as those in the S&P 500, as well as that of middle-sized and small U.S. companies and foreign companies, Fitzgerald said. Some investors might even include real estate, too, he said.

A good, simple approach for the average investor would be to buy a target-date fund, he said. These are well-diversified funds that automatically toggle asset allocation based on an investor’s age.

His firm’s average 60-40 stock-bond portfolio currently allocates about 11.5% of its total holdings to the S&P 500 index, Fitzgerald said.