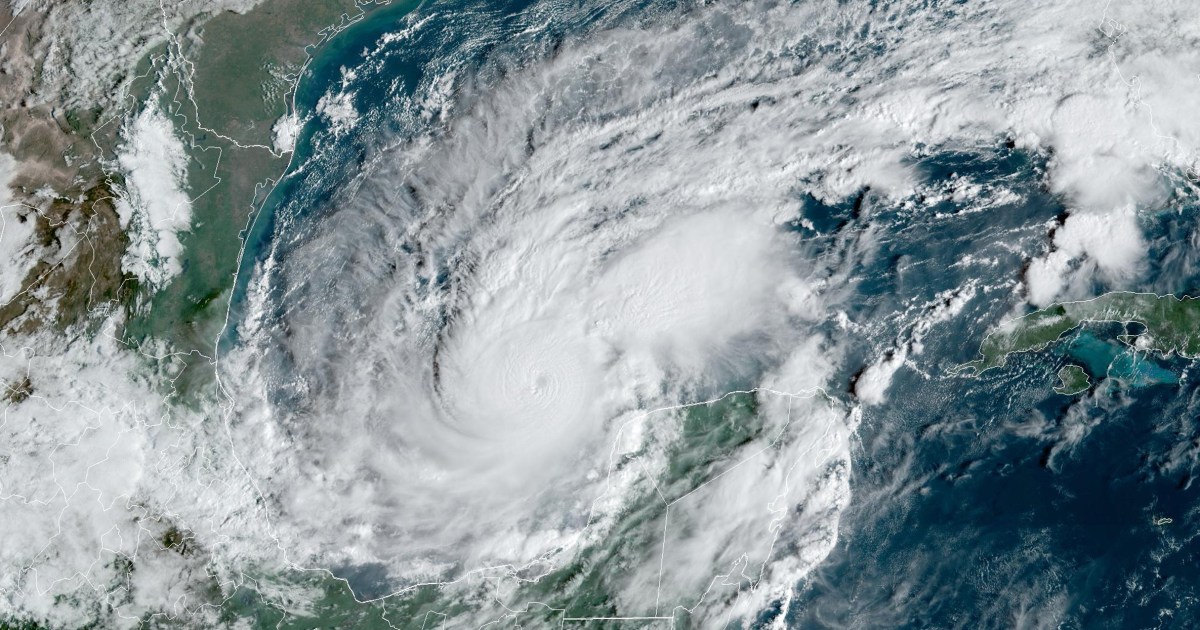

Milton, which is expected to make landfall Wednesday evening along Florida’s Gulf coast, has been traveling over unusually warm waters in the Gulf of Mexico. Much of the ocean basin has been well over 80 degrees Fahrenheit, with parts of the Gulf up to 4 degrees higher than normal, according to data from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Elevated temperatures in the Gulf also helped Hurricane Helene gather strength before it made landfall in Florida’s Big Bend region less than two weeks ago.

A 2023 study published in the journal Scientific Reports found that tropical cyclones in the Atlantic Ocean were around 29% more likely to undergo rapid intensification from 2001 to 2020, compared to 1971 to 1990.

Scientists have recorded many other recent examples of rapid intensification, including Hurricane Harvey in 2017, Hurricane Laura in 2020, Hurricane Ida in 2021 and Hurricane Idalia last year. In 2019, Hurricane Dorian’s peak winds increased from 150 mph to 185 mph in nine hours, and Hurricane Ian in 2022 underwent two rounds of rapid intensification before it made landfall in Florida.

Although the process is well documented, rapid intensification is challenging to forecast. Scientists know the ingredients needed to jump-start the phenomenon, but accurately predicting when and how it will happen — and its precise catalyst — remains tricky.

Milton is expected to weaken slightly before making landfall, but the storm’s impact will be severe. A storm surge watch is in effect for Florida’s Gulf Coast, which includes the Tampa Bay area, where potentially life-threatening storm surge up to 12 feet is forecasted. As many as 15 million people are under flood watches across the state.