CNN

—

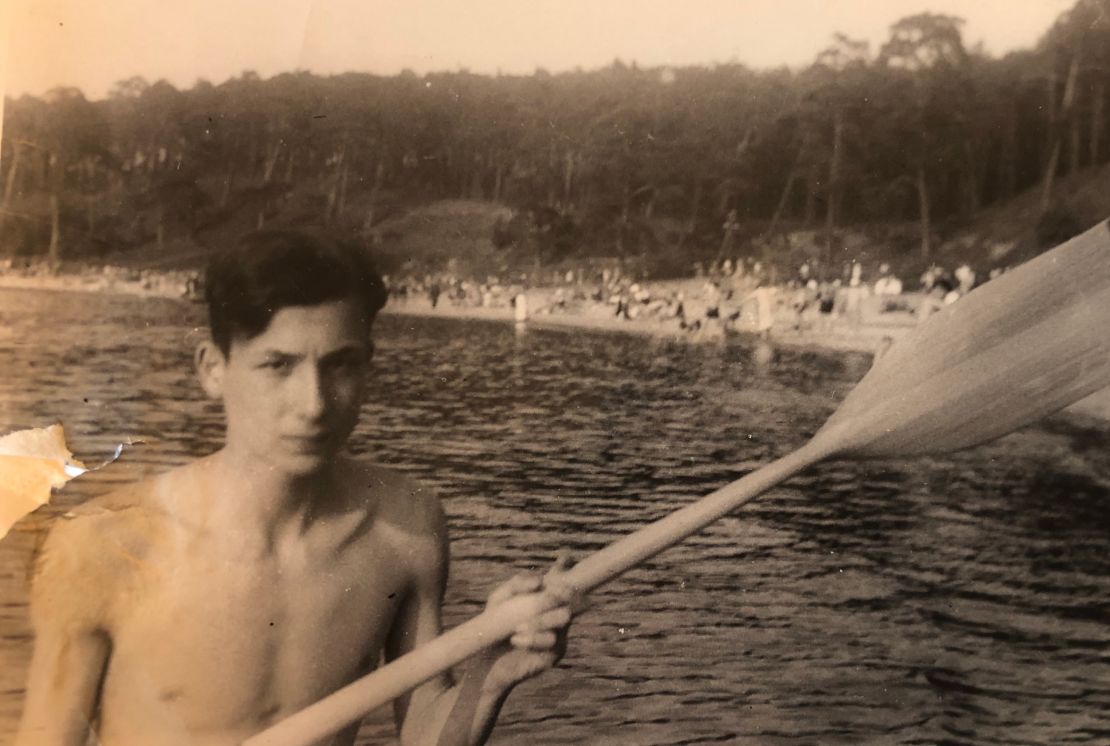

After Germany hosted the England soccer team in May 1938, Rolf Friedland waited patiently outside the stadium.

The teenager was hoping to speak to some of soccer’s biggest stars of the time – a feeling of anticipation that many sports fans have experienced.

But for the German-Jewish 17-year-old, a lot more was at stake. Friedland knew that one of the soccer players who lined up that day had the power to save his life.

And it was with the help of an England defender that Friedland was able to leave Germany, escape the persecution of the Nazis and start a new life overseas as Ralph Freeman.

‘They’re going to kill me’

Freeman’s family had already fled Germany without him, and he was left alone and isolated, knowing that leaving the country was essential for his survival.

“Psychologically, he was desperate to get out,” Ralph’s son Alan Freeman told CNN. “He was left there alone presumably with some sort of hope that his parents would be able to get him out, but I don’t think he entirely relied on that.”

A lifelong soccer fan, Freeman’s desperation to leave Nazi Germany led him to the Olympiastadion on that fateful day on May 14, 1938. He hatched a plan to try and gain the attention of an England player who could aid in his escape from Germany.

“I think that my dad was a creative individual and to do something like that, you need a degree of creativity,” explains Alan.

“While there was a certain element of creative initiative, I think that it [the plan] was principally done out of desperation,” he added.

“’I just need to get out,’” said Alan of his father’s attitude. “’I’ll find any way to try and get out of it. If I don’t get out of here, they’re going to kill me.’”

When the players made their exit from the stadium, it was England and Tottenham Hotspur defender Bert Sproston who stopped and listened to Freeman.

“I’m not sure that he especially singled out Bert Sproston as the most likely person to help him,” Alan said. “He simply spoke to that particular player and that particular player registered my father’s desperation.

“It obviously touched his heart and he decided to go back and do something about it.”

While Sproston would not have known the exact details of what life was like for a Jewish person living in Germany at the time, author and journalist John Leonard thinks he would have been aware of the Nazis’ hostility towards Jews.

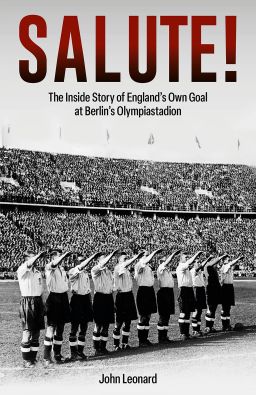

In his book ‘Salute!’ Leonard looks at the how sport and politics clashed during this time – culminating in this famous match.

“I’m sure he did realize that for Jewish people in Germany that, to put it politely, they were in for a hard time,” Leonard told CNN.

Michael Berkowitz, professor of modern Jewish history at University College London, agreed.

“Everyone was aware of it,” Berkowitz told CNN. “It’s again important not to read backwards, but people did know that there was something going on that was just not normal by the standards of other places.”

After speaking to Sproston, who took his details back to Britain, Freeman was granted a visa to the UK to watch England play in a friendly game.

He was finally able to leave Germany and avoid the events that would soon unfold.

‘A crucial year’

Europe was on the brink of war when England headed to Berlin in 1938.

Geopolitical tensions were nearing a boiling point on the continent and Adolf Hitler and the Nazi party’s power continued to grow throughout Europe.

As the Nazis’ influence increased, the treatment of the Jewish population of Germany dramatically worsened.

“1938 was a really crucial year,” Berkowitz said.

This was the year which saw the German annexation of Austria, commonly known as the Anschluss, in March as well as Kristallnacht – the night of broken glass – in November of that year.

Berkowitz explained that Hitler cautiously ramped up his abhorrent treatment of Jews after he came to power in 1933 but 1938 saw conditions dramatically worsen.

“Included in the annexation of Austria is incredible anti-Jewish action, including the burning of synagogues and Jews being beaten up on the streets,” Berkowitz added.

“But then even more striking was … what would later be called Kristallnacht,” Berkowitz said. “Almost all of the synagogues in Germany were burnt down, literally hundreds, thousands of people beaten up in the streets [and], it was thought at first that there weren’t that many people killed, now we know that there were many more people killed.”

According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, at least 91 Jews were killed, 30,000 German Jewish men were arrested and sent to concentration camps and hundreds of synagogues were set on fire during the events of November 9 and 10 1938.

“That was when the world really woke up. Unified in horror at what the Nazis were up to,” Leonard said.

Thanks to Sproston’s intervention, Freeman was able to board a train from Berlin and arrived in London just a matter of weeks before the events of November 9-10 unfolded.

‘He saved his life’

Sproston’s connections through the footballing world proved to be vital in helping Freeman leave Germany.

“You usually would need some sort of personal connection. You need someone to vouch for you, or you need to come in through some sort of organizational effort,” Berkowitz said of the process of obtaining a visa to leave Germany as a Jew.

“But just say purely as an individual or an individual without means.

Wow. This is not easy to do.”

Sproston sponsoring Freeman’s UK visa therefore proved invaluable to ensuring his escape from Germany.

“Not only did Bert Sproston change Ralph Freeman’s life. He saved his life,” Leonard added.

“Without his intervention the chances were that young Ralph Freeman would have ended up in a concentration camp, and he would have been murdered by the Nazis.”

Leonard also said that unlike the majority of his England teammates, Sproston could look back on this game with a sense of pride.

It was before this game that the England players famously performed the Nazi salute prior to kick off.

Leonard stated that the England team was under considerable pressure to perform the Nazi salute as a form of appeasement but, by helping Freeman, Sproston can feel less guilty about the pre-match salute.

“He [Sproston] was one of the players who left Berlin, after making a personal decision, as much as a team decision, that would haunt most of the players for the rest of their lives – he certainly could look back on that game with a touch of pride,” said Leonard.

‘The world would be a better place’

Sproston passed away in 2000 and Ralph Freeman passed away in 2010, but Ralph’s son Alan said the pair remained close after their first interaction.

“To the day that Bert died they were in contact,” Alan explained.

Alan added that the pair were always pleased to see each other, and this good relationship has been passed on to the next generation as Alan keeps in touch with Janice, Sproston’s daughter-in-law.

Alan said he and Janice have a “deep, meaningful relationship and a friendship,” built on the legacies and stories of their father and father-in-law.

A love for football, and in particular Tottenham Hotspur, was also passed down from father to son and Alan fondly remembers following Tottenham with his father.

But more importantly, so did the story of Bert Sproston helping Ralph Freeman in his bid to leave Nazi Germany.

“I just think that if all of us could just act with decency to other people in the way that Bert behaved towards my dad, then the world would be a better place,” Alan said.