After trudging upslope for weeks, a giant tortoise slows its hundreds of cumbersome kilograms to a stop. Dense woods defended by barbed wire–like blackberry bushes block its path. After a brief foray into the painful prickles, the tortoise backs out and plods on, searching for a way out of the woods.

These blackberry-lined forests of Spanish cedar trees (Cedrela odorata) are invasive in the tortoise’s island home in the Galápagos. If they can, these titanic turtles stay clear of the new, troublesome habitats on their seasonal uphill treks to find food, researchers report in the February Ecology and Evolution. If the Cedrela forests one day manage to block the shelled reptile’s migration altogether, the consequences for the tortoises and the surrounding island ecosystem could be dire, researchers say.

Wildlife biologist Stephen Blake and his colleagues have been studying the movements of Western Santa Cruz tortoises (Chelonoidis niger porteri) since 2009. Tracking the reptiles’ positions with GPS tags and other mobile instruments previously revealed that some tortoises embark on weeks-long migrations to the highlands of Santa Cruz Island — as much as 400 meters above sea level over two to four weeks — and back. These traveling tortoises tend to be large and thus potentially vulnerable to food shortages: They lumber uphill during the dry season to feed on the higher-elevation vegetation that flourishes under a moist cloud bank.

“They’re basically doing the same thing that Serengeti wildebeest or Canadian elk do,” says Blake, of Saint Louis University in Missouri. “They follow the green.”

Stephen Blake

Years into the tortoise tracking project, Blake noticed that the reptile’s migration corridors appeared to line up with gaps in the highly invasive Spanish cedars that were visible in satellite images on Google Earth. The next logical question: Were the forests a problem for the critically-endangered tortoises?

The researchers analyzed about 10 years of migration data from 25 tagged adult tortoises, and overlaid 140 migration routes atop a map of Spanish cedar forests on the island. Most tortoises favored funneling into small gaps between Cedrela stands, one of which is only about 140 meters wide at its narrowest and two others around a kilometer and half a kilometer wide each. This is fairly slim compared with the island’s 40-kilometer width, especially when considering how thousands of tortoises might converge on these strips between July and November each year to march uphill. Only 12 trips made by three tortoises went through large patches of forest, and five tortoises consistently stopped their migration either right inside or at the blackberry border of a forest.

“We’ve seen a few tortoises sort of bludgeon their way in through these thick patches of blackberry and can’t move,” Blake says. Some turn around and walk back out. For those that make it through, the cedar forest interior is well shaded, which Blake and his colleagues think makes it harder for the tortoises to stay warm. There’s also little food in there. “It’s just not an environment that they want to be spending a week trying to walk through,” he says.

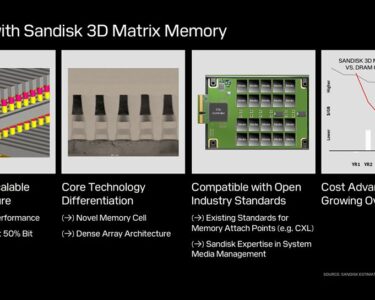

Tortoise tracks

This map shows 140 migratory paths (gray and black tracks) taken by Western Santa Cruz tortoises in the southwestern corner of Santa Cruz Island in the Galápagos over 10 years. Most of the tortoises avoided cedar forests (green patches): Gray paths show segments walked outside of the forests and black mark segments walked within the forest. Tortoises mainly traveled through three small gaps (A, B and C) in the forest.

Ten years of Western Santa Cruz tortoise migration routes

It’s still unknown if the available corridors through cedar patches could be closed by the trees’ spread. But if migration routes are choked off, the tortoises might be forced to eat a suboptimal diet, which could hurt the animals’ growth, health and reproduction, Blake says. The tortoises also spread seeds, turn up soil, bulldoze vegetation and create microhabitats wherever they shamble. Disrupting their travels may constrain their ecological influence.

It wouldn’t be the first time invasive species precipitated reverberations throughout an ecosystem (SN: 1/25/24). Specifically, plant invasions can have major impacts on animal behavior, says Peter Stewart, an ecologist at the University of Stirling in Scotland who published a literature review of these effects in 2021. Invasive plants can alter “the ways that animals communicate, where they build their nests and lay their eggs, how they hunt for prey or avoid their own predators, and more,” Stewart says. “These behavioral changes can have some quite profound consequences for the animal species, as well as for the wider ecosystem and for people.”

Countering the Cedrela invasion is a thorny task. Removing the trees could just allow a sea of blackberries to take their place, Blake points out, creating new problems. Additionally, the trees’ high-value timber is important to the local economy. Somewhat paradoxically, the invasive trees are considered vulnerable to extinction by the International Union for Conservation of Nature in their native ranges in Central America, the Caribbean and much of mainland South America.

The trees now grow throughout the Galápagos and are generally “devastating” to native ecosystems, Blake says. More research on where and how fast the cedars are spreading — and if they can be effectively removed — is crucial.