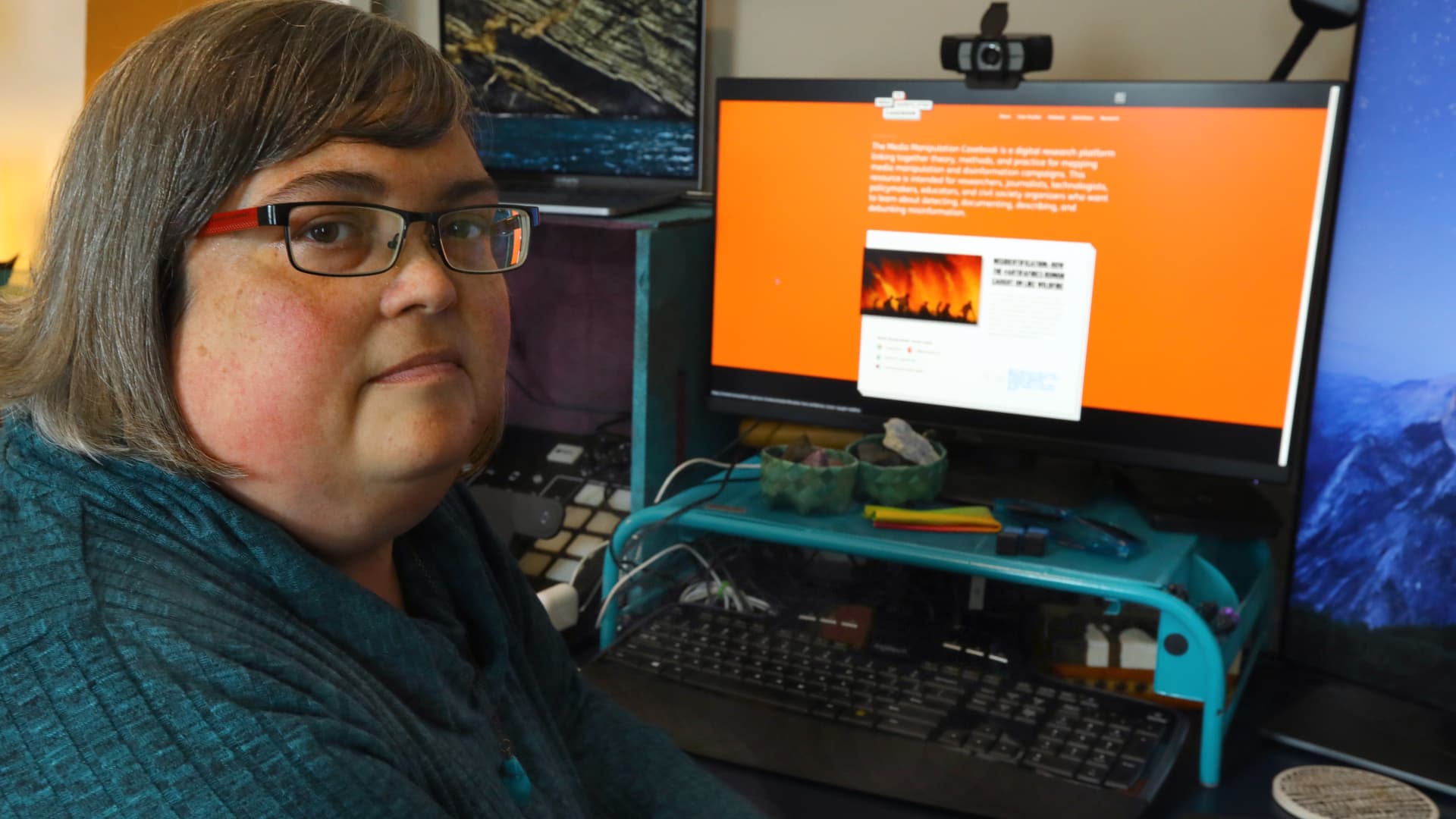

WASHINGTON — Social media researcher Joan Donovan says she knows the exact moment her career began to go off the rails.

The moment led to her departure from Harvard University in what she calls a firing, which Harvard says was anything but. The resulting dispute has real-world implications for academic freedom, social media and corporate influence over research.

On Oct. 29, 2021, Donovan, a Harvard research director focused on social media and disinformation, says she was invited to address a prestigious group of wealthy donors to Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government, known as the Dean’s Council.

The meeting took place over Zoom, and donors logged on from their homes and offices. Donovan says she had been invited to present the findings of her research to the group – a plum assignment she believed was due to the prominence and importance of her work.

“I was so excited,” Donovan told CNBC. “I thought that this is an amazing validation of the work that I had been doing.”

Donovan began to brief the donors on her research into internet disinformation and its impact on American society. The meeting fell just weeks after an explosive moment in social media: A former employee of Meta, still called Facebook at the time, named Frances Haugen turned whistleblower and went public with a secret trove of thousands of pages of internal documents from the tech giant.

Haugen had testified before Congress on Oct. 5 that the documents revealed Facebook knew its services were causing social harm, spreading misinformation and hurting teenagers. But she said the company chose profits over safety.

Now Donovan shared a bombshell of her own with the Harvard donors: She told them that she, too, had obtained the trove of documents, a massive file she considered the “most important documents in internet history.”

She laid out an argument similar to the one Haugen had been making on national television: Facebook knew of the harm its services caused, but chose to do nothing.

Central to Donovan’s thinking was the idea that Facebook was not just a victim of bad guys who exploited new technology for their own ends, but that Facebook actually designed systems that incentivized the most provocative content.

“The problem was that the design of the technology itself — social media itself, was giving bad actors a first mover advantage, especially when it came to novel and outrageous content, which is what goes viral,” she told CNBC in an interview.

In other words, Donovan said, what was going wrong was not necessarily in the world outside Facebook, but inside the company’s algorithms.

When Donovan finished explaining her findings on the Zoom call, she says she noticed one man on her screen raising his hand eagerly to speak. He was Elliot Schrage, a member of the Dean’s Council donor group at Harvard and a former vice president of global communications and public policy at Facebook.

Donovan says Schrage disagreed sharply with her criticism of Facebook – so intensely that after the meeting wrapped up, Donovan sent a text to her superior at the Kennedy School, asking, “Should I be worried about the way Schrage got mad at me?”

“I think we should have worried if he DIDN’T get mad,” the supervisor replied, according to a text message transcript provided to CNBC.

“I thought you were just terrific. So sophisticated and fair in your thinking and analysis. Made me proud.”

Schrage declined to comment.

Facebook has publicly denied allegations that it turns a blind eye to harms caused by its services in order to profit from them.

In a lengthy response to a 2021 Wall Street Journal series based on allegations made by Haugen, the whistleblower, Facebook’s vice president of global affairs and communications, Nick Clegg, wrote this: “At the heart of this series is an allegation that is just plain false: that Facebook conducts research and then systematically and willfully ignores it if the findings are inconvenient for the company.”

“It’s a claim which could only be made by cherry-picking selective quotes from individual pieces of leaked material in a way that presents complex and nuanced issues as if there is only ever one right answer,” wrote Clegg.

As Donovan tells it, support from her superiors didn’t last long after she dove into her Facebook research.

In early November, the then-dean of the Kennedy School, Douglas Elmendorf, emailed Donovan to follow up on the Dean’s Council meeting, with questions about her research into Facebook. The company had changed its name to Meta on Oct. 28.

Among the issues he said he wanted to address, according to a copy of the email provided to CNBC, were “How you define the problem of misinformation for both analysis and possible responses (algorithm-adjusting or policy making) when there is no independent arbiter of truth.” And he said he would like to know “How the research you’re conducting provides a basis for comments you’re making about current events.”

The email alarmed Donovan, who believed the language in it echoed talking points Facebook executives had been using publicly. And she says she knew that Dean Elmendorf had a close personal relationship with Sheryl Sandberg, the then-chief operating officer of Facebook’s parent company, Meta Platforms.

Elmendorf had been Sandberg’s undergraduate advisor at Harvard, and Sandberg herself was a multimillion-dollar donor to Harvard’s Kennedy School. Elmendorf attended Sandberg’s wedding in the summer of 2022.

“I got called into the principal’s office and was questioned about why I’m talking about Facebook,” Donovan said. “Interestingly, the dean never asked me about Twitter or YouTube or, you know, Google, which we also investigated. It was really about having the internal papers at Facebook and what we plan to do with them.”

Through a Harvard spokesman, Elmendorf declined to comment for the record.

Through an employee, Sandberg declined to comment. Harvard officials told The Washington Post that Elmendorf and Sandberg never discussed Donovan.

The next month, a charity operated by Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg and his wife Priscilla Chan – both themselves former Harvard students – made an extraordinary announcement: It was pledging a half-billion dollars over 15 years to create a new institute at Harvard for the study of artificial intelligence, to be named after Zuckerberg’s mother’s family.

The scale of the contribution – and its intended use – raised eyebrows on campus. A column in the Harvard Crimson written by two undergraduates called acceptance of the donation a “damning misstep by our institution.”

The students, Guillermo S. Hava and Eleanor V. Wikstrom, wrote: “Our institution — our entire elite higher education system, arguably — has a penchant for auctioning off academic priorities to the highest bidder.” The Crimson column did not mention Donovan.

The December 2021 gift was the biggest, but not the first, Chan Zuckerberg Initiative donation to Harvard: Since 2018, the foundation’s disclosures show it has bestowed Harvard or entities affiliated with it with dozens of grants worth multiple millions of dollars.

Donovan says her position at Harvard became increasingly untenable, as the months went on. She came to believe that administrators wanted her to leave. “I became persona non grata when I turned my attention specifically to Facebook,” says Donovan.

The situation came to a head in a meeting with Elmendorf in the summer of 2022, Donovan says, at which the dean told her she would have to wind down her program, known as the Technology and Social Change Research Project, by June 2024.

Donovan says Elmendorf also told her during the meeting, “I want you to know that you do not have academic freedom,” adding “I want to remind you that you’re staff here.”

As a staff member, Donovan was not afforded the same protections that are extended to tenured professors.

Donovan felt constrained, and says she was told that for the remainder of the project she could not start any new projects or hire additional staffers.

“That to me is an egregious and anti-intellectual obstruction of academic freedom,” Donovan said. “It contradicts the entire reason why a university exists, which is to share the light with the world.”

On July 13, nearly a year before the date she says she had been given for the conclusion of her project, Donovan says she was informed that Harvard was ending the project on Aug. 31 and that her role as research director was being eliminated.

Donovan’s account of her departure was laid out in a disclosure document sent to Harvard on Nov. 28 by Whistleblower Aid, the same nonprofit group that worked with Facebook whistleblower Haugen in 2021.

Whistleblower Aid sent Donovan’s allegations to the Office of the Attorney General of Massachusetts, which is reviewing the material, according to an official.

The group also raised Donovan’s allegations with the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights. A spokesperson for the department said the office does not confirm or deny the existence of complaints.

In a statement to CNBC, Harvard Kennedy School Director of Public Affairs James Smith disputed Donovan’s account of her departure. “The document’s allegations of unfair treatment and donor interference are false,” Smith said. “The narrative is full of inaccuracies and baseless insinuations, particularly the suggestion that Harvard Kennedy School allowed Facebook to dictate its approach to research.”

Smith explained that Donovan’s situation was related to her employment status at the university. “By longstanding policy to uphold academic standards, all research projects at Harvard Kennedy School need to be led by faculty members,” he said.

“Joan Donovan was hired as a staff member (not a faculty member) to manage a media manipulation project. When the original faculty leader of the project left Harvard, the School tried for some time to identify another faculty member who had time and interest to lead the project. After that effort did not succeed, the project was given more than a year to wind down. Joan Donovan was not fired, and most members of the research team chose to remain at the School in new roles.”

Donovan concludes that the core finding of her research was antithetical to Facebook, and ultimately to Harvard.

“I believe Harvard took me out because I was not toeing the company line about platforms, which is you can stay safe from companies if you suggest that this is a whole of the internet problem,” she said. “Social media is not to blame.”

What she had concluded about Facebook was quite the opposite – the design of social media itself was causing problems: “I was picking apart their design and saying the way this works is enabling genocide, terrorism, hate, harassment, incitement.”

Donovan was out.

“Harvard hastened my exit by firing me,” she said. “But I feel really good about what we did to make sure that my team was safe, to make sure that the information that needed to get out there was out there.”

Smith told CNBC that Harvard University and the Kennedy School continue to carry out misinformation and social media research to this day. He noted that a faculty member constructed and posted online the Facebook Archive, consisting of documents originally leaked by Haugen.

In October, the Kennedy School’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics, and Public Policy and Harvard’s Public Interest Tech Lab jointly published the Facebook Archive, containing the documents obtained by Haugen in a searchable database open to the public at FBarchive.org.

A spokesperson for Meta declined to comment.

A spokesperson for the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative said the organization, “had no involvement in Dr. Donovan’s departure from Harvard and was unaware of that development before public reporting on it.”