CNN

—

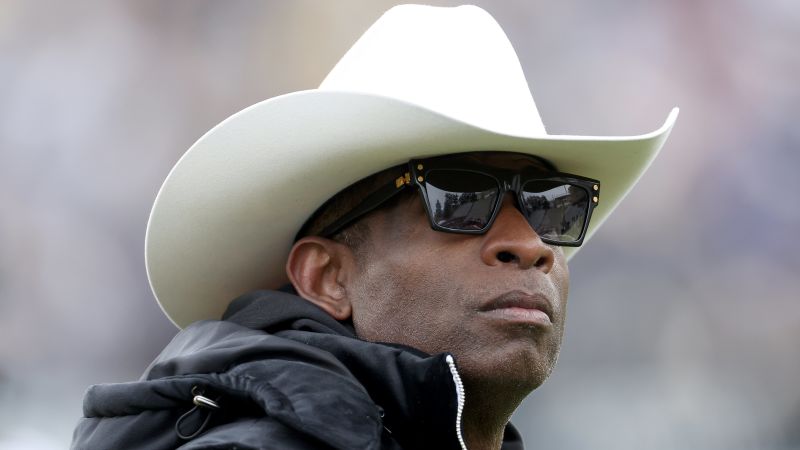

After his team’s first victory earlier this month, University of Colorado football coach Deion Sanders said something remarkable. He talked bluntly about racism and football in a way that few Black coaches at an elite level are willing to do.

“We’re doing things that have never been done, and that makes people uncomfortable,” Sanders said. “When you see a confident Black man sitting up here talking his talk, walking his walk, coaching 75% African Americans in the locker room, that’s kind of threatening. Oh, they don’t like that.”

We know what Sanders’ critics say. He’s got a big mouth. He plays the race card when he should just coach football. His “hype train is about to derail.”

But as at least one columnist has noted, Sanders also embodies the “audacious Blackness” that so many African Americans hunger for right now.

Black America’s embrace of Sanders and his team is now well-documented. One Black commentator has compared him to Muhammad Ali. Numerous Black celebrities, from rappers Master P and Lil Wayne to LA Clippers forward Kawhi Leonard and actor Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson, have made appearances at his games.

Sanders has even joked someone told him that by the time Colorado plays USC next week the stadium in Boulder is “going to look like the BET Awards.”

The Buffaloes are now, according to one commentator, “Black America’s team.” They’re following in the footsteps of the Georgetown Hoyas men’s basketball teams of the 1980s, the University of Miami football team of the late ‘80s and the UNLV and Michigan “Fab Five” hoops teams of the early ‘90s, all of whom had strong Black identities and followings.

“It doesn’t matter who you rooted for before or even still do now, if you don’t even particularly care about college football, brothers and sisters, you probably care about Sanders and his team,” Clinton Yates said in a recent column for Andscape, a Black-led media platform dedicated to stories about Black identity.

But those who look to the past to explain Sanders’ soaring popularity miss why the present also plays a huge role. His success cannot be separated from the political and cultural climate in Black America. Sanders may be an athlete, but he’s taking on some of the same foes many Black Americans face in their daily lives today.

And he’s the type of hero many Black Americans are looking for right now, for at least two reasons.

He refuses to code switch

It’s not like Black America has had much to cheer for in recent years. Former President Obama has long departed the national spotlight. The so-called George Floyd racial reckoning in 2020 now seem as remote as the disco era. A conservative majority on the US Supreme Court recently eviscerated affirmative action in higher education. Black books and history are being banned from classrooms. And White supremacists continue to gun down Black people in public.

Enter “Coach Prime.”

Sanders represent one of those rare moments of contemporary racial progress. He has entered one of the Whitest and most conservative institutions in America — college football — and excelled. While many college football players are Black, most of the top teams are coached by White men, and many of the best teams are in red states like Alabama, Georgia and Louisiana. It’s not unusual to see Black and brown players competing on stadium turf surrounded by cheering White spectators.

And it’s not just college — the entire culture of elite football is run by White men. The NFL is largely dominated by White, politically conservative team owners. It’s no secret the league has had a poor record of hiring Black coaches.

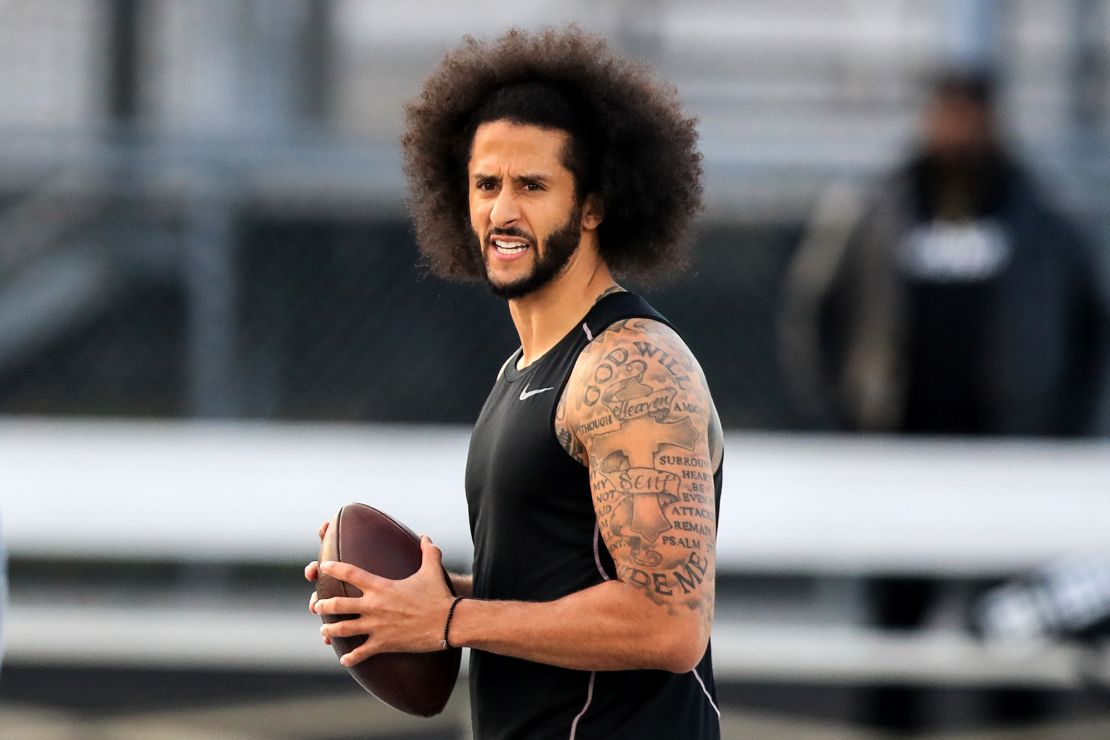

It’s also no secret what happens when an outspoken Black athlete like former NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick speaks openly about race in a way that makes some White people uncomfortable. They are punished.

This type of punishment is something that many Black people who have never touched a football can relate to. Get angry in the workplace, give a police officer the wrong look, visit a neighborhood where someone decides you look “suspicious,” and you can lose your livelihood, or worse, your life.

But Sanders doesn’t seem to care what White people think. He exhibits little fear about what they will do to him. He’s blunt and joyful and refuses to “code switch,” or change his demeanor and behavior to make White people comfortable. He’ll bring up racism at a press conference where others might prefer he just shut up and talk about football.

For many Black people, this “unapologetic Blackness” is exhilarating.

“I love it when he says, ‘I told ya so.’ I love that he refuses to play the game of false humility,” Greg Moore wrote in a recent Arizona Republic column. “I love that he’s changing the face of college football.”

He’s destroying stereotypes about Black people

In sports, some of the biggest battles Black people have fought have not been on the field but in the arena of perceptions.

For years, no major league baseball team would hire a Black manager or general manager. In 1987, Al Campanis, then the general manager for the Los Angeles Dodgers, was fired after he said in a televised interview that Black people did not have the “necessities’ to run baseball teams.

Black men weren’t considered intelligent enough to play quarterback, a stereotype quarterback Doug Williams largely erased when he won the Super Bowl in 1988 with the Washington Redskins. Black coaches are still hugely underrepresented in the NFL, a league where more than half the players are Black.

The struggle to slay racial stereotypes is familiar to many Black people. Throughout history, Blacks have told White America: Give me an equal chance and watch me excel.

Sanders represents proof that given an equal chance and resources, Black people can win.

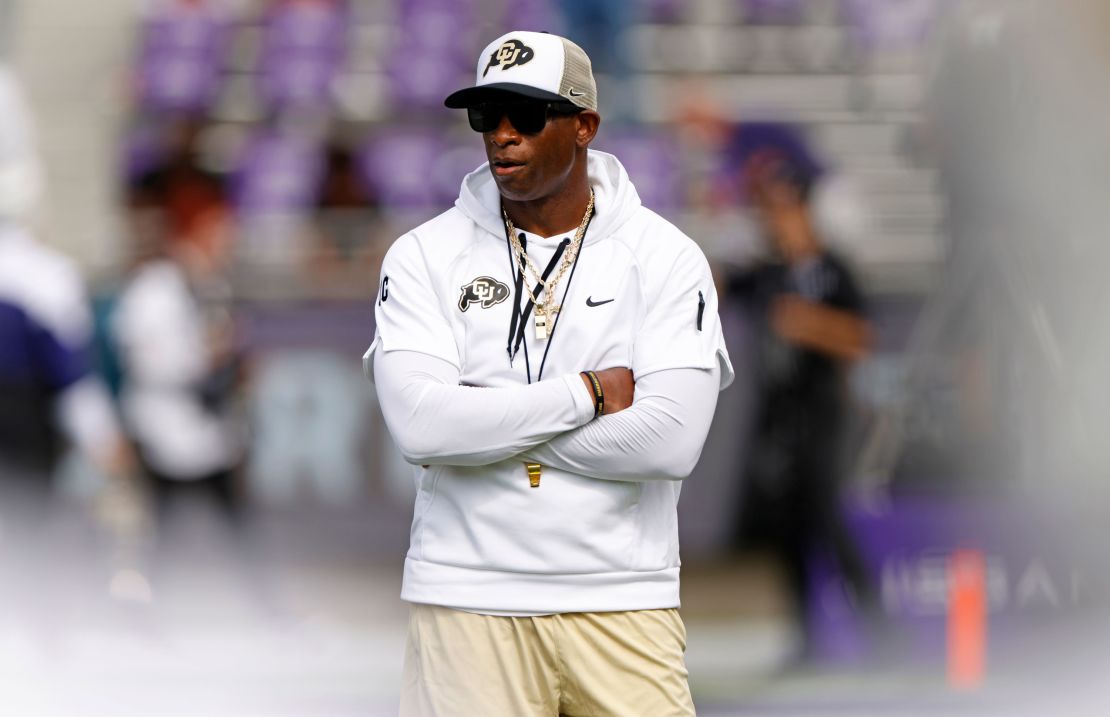

That should not be any surprise to anyone who has followed his career. Sanders is a first-ballot NFL Hall of Famer and remains the only athlete ever to play in both a World Series and a Super Bowl. Before he took the job at Colorado he was head football coach at Jackson State University, a historically Black college in Mississippi, where he built a winning program and raised awareness of HBCUs.

“I’m going to win. But not only win, but dominate,” Sanders said in a recent “60 Minutes” interview. “That’s what I do. That’s who I am.”

Sanders upset some people in the Black community for leaving an HBCU for a traditionally White school. He also drew some fire for quickly replacing most of Colorado’s players.

But he’s also defeated racial stereotypes in areas that extend beyond sports.

Consider his relationships with his sons. Sanders has five children, including two star players on his team. His son, Shedeur, is the starting quarterback and a probable NFL draftee. The other, Shilo, is a safety.

Sanders jokes about ranking his children based on their performance, similar to sports power rankings. Some of the best clips from his interviews show his warm interaction with his sons, who radiate love and respect for their father.

This has a powerful impact on Black Americans, whose men are often described as absentee fathers missing from their sons’ lives. When he was head coach at Jackson State, one Black commentator noted how powerful it was to see Shedeur Sanders throw a touchdown and then run over to hug his father, who was confined to a wheelchair after recent leg surgery.

“With imagery of absent or deadbeat black fathers being the dominant image of black families, it was critical to see that all black fathers are not that way,” Vaughn Wilson wrote. Sanders and his sons have a bond that is an example for not only their teammates, but for everyone.

Racial stereotypes become deadlier when their victims start to believe them. For so long, elite Black athletes felt like they had to go to White colleges and play for White coaches to excel. Sanders is showing that a Black coach can not only recruit some of the best Black talent in the country but compete at an elite level.

Ted Johnson, a columnist at the Washington Post, recently alluded to these stereotypes during a podcast about Sanders. He said that when someone is raised in a country that routinely tells them that they get promotions because of affirmative action, it’s easy to wonder if those critics are right.

“And then someone like Deion comes along,” Johnson said. “It’s proof we can be successful, and we are given the ability to showcase our talents and personalities. We can be successful at any level. And that point of pride—it cannot be overstated.”

There’s already talk that Sanders may disrupt college football in profound ways beyond the playing field. He may pave the way for more Black coaches at top schools. He may also show that charismatic Black coaches can lure top prospects away from powerhouse college teams.

He’s brought an “audacious Blackness” to college football that’s revolutionary, one commentator says.

“Sanders is a showman and marketer, but more importantly, he is an unapologetic Black man,” said Bakari K. Lumumba in a recent column for the Pan African Voice. “The (college football) industry concomitantly relies heavily on Black athletes to fill stadiums, attract lucrative television contracts and annually pay white coaches a king’s ransom. In many ways, the profession at this level has become welfare for white coaches. Sanders is attempting to stop the gravy train.”

The Sanders’ hype train may derail when his team takes on the higher-ranked Oregon Ducks on Saturday. An injury to a key player could throw the season.

And Sanders may not be able to dominate big-time college football as he did so memorably as a baseball star and one of the most gifted cornerbacks the NFL has ever seen.

But for Black Americans who are hungry for any kind of win, what Sanders has accomplished already makes him a champion.

John Blake is the author of “More Than I Imagined: What a Black Man Discovered About the White Mother He Never Knew.”