CNN

—

The 2022 World Cup final will go down as one of the most exciting, dramatic and memorable matches in the history of the game.

It was the scene of Lionel Messi’s greatest moment on a soccer pitch, in which he cemented his legacy as the best player of his generation after finally guiding Argentina to World Cup glory.

It was, for many, the perfect, fairytale ending to a tournament which thrilled well over a billion fans around the world. So good, perhaps, that many forgot it bookended the most controversial World Cup in history.

Rewind to the start of the tournament and the talk was all about matters off the field: from workers’ rights to the treatment of the LGBTQ+ community.

Just hours before the opening match, FIFA President Gianni Infantino launched into a near hour-long tirade to hundreds of journalists at a press conference in Doha, where he accused Western critics of hypocrisy and racism.

“Reform and change takes time. It took hundreds of years in our countries in Europe. It takes time everywhere, the only way to get results is by engaging […] not by shouting,” said Infantino.

At one point, the FIFA president challenged the room of journalists, stressing FIFA will protect the legacy for migrant workers that it set out with the Qatar authorities.

“I’ll be back, we’ll be here to check, don’t worry, because you will be gone,” he said.

So, a year on from the World Cup final, what is the legacy of the 2022 World Cup?

Human cost of hosting the World Cup

Human rights groups were unequivocal in their condemnation regarding Qatar hosting the World Cup.

In a 2021 report, Amnesty International said that Qatari authorities had not investigated “thousands” of deaths of migrant workers over the past decade “despite evidence of links between premature deaths and unsafe working conditions.”

The same year, The Guardian reported that 6,500 South Asian migrant workers died in Qatar since the country was awarded the World Cup in 2010. The report did not connect all 6,500 deaths with World Cup infrastructure projects and was not independently verified by CNN.

Hassan Al Thawadi, the man in charge of leading Qatar’s preparations, told CNN’s Becky Anderson that the Guardian’s 6,500-death figure was a “sensational headline” that was misleading and that the report lacked context.

Al-Thawadi later told Piers Morgan that between 400 and 500 migrant workers died as a result of work done on any project connected to the tournament – a greater figure than Qatari officials had initially cited.

He clarified that three work-related deaths were linked specifically to the construction of World Cup stadiums, as were 37 non-work-related deaths.

In truth, no one really knows the human cost of hosting the World Cup in a country which had to build much of its infrastructure from scratch, relying heavily on migrants working during the scorching summer heat.

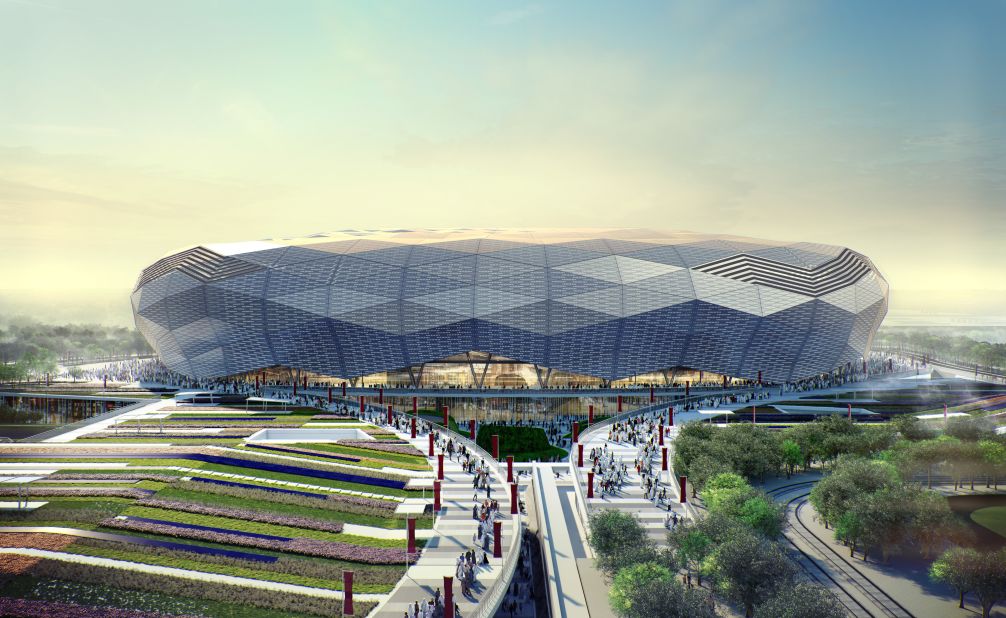

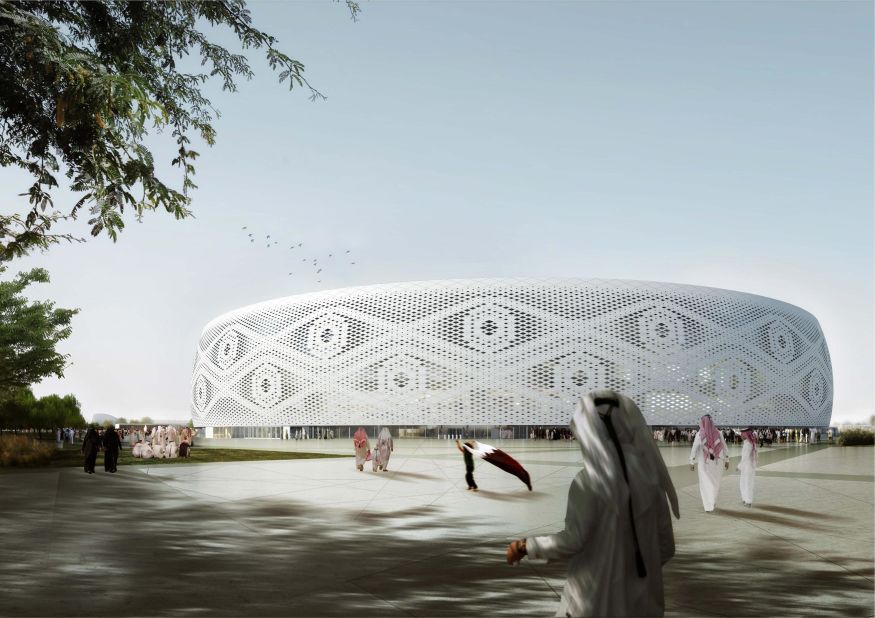

The stadiums used for the tournament were undeniably impressive. Some are now used for cultural and sporting events, while others are left vacant for periods of time.

Amid it all, Qatar promised reform for workers, but did that ever materialize?

Take a tour of the Qatar 2022 World Cup stadiums

A year on from the tournament, Amnesty said the legacy for migrant workers in Qatar was in “serious peril.”

In a briefing titled “A Legacy in Jeopardy,” the leading human rights organization said that it “finds that just as the glare of the world’s media spotlight dimmed, so too did the [Qatar] government’s push for fair conditions and decent work for the hundreds of thousands of men and women who helped realize Qatar’s World Cup dream and will continue to keep the country moving for many years to come.”

Amnesty acknowledged that some previous issues had been improved – workers were able to leave the country and are more freely able to change jobs, with the much-criticized kafala system a thing of the past.

However, the organization maintained that, despite FIFA and Qatar’s claims of progress, not enough has been done since the World Cup festival left town.

Amnesty said it spoke to workers who say permission is still required to facilitate job transfers, while wage theft remains the most frequent form of exploitation.

“The workers who made the 2022 World Cup possible must not be forgotten,” Amnesty urged.

In a statement sent to CNN, Qatar’s International Media Office (IMO), which was set up to “present an accurate image of Qatar,” said reforms were accelerated by the World Cup, “creating a significant and lasting tournament legacy.”

“The commitment to strengthen Qatar’s labour system and safeguard workers’ rights was never an initiative tied to the World Cup and was always intended to continue long after the tournament ended,” the statement added.

It added: “One year on from the World Cup, Qatar’s commitment to labour reform remains as strong as ever as we strive to establish a world-leading labour system that attracts people from all over the world to live and work in Qatar.”

‘Significant progress’

FIFA has been on the defensive ever since announcing Qatar would host the tournament 13 years ago.

Amid the criticism, it set up a World Cup Legacy Fund which it said would focus on children’s education in developing countries, while “establishing a labour excellence hub.”

FIFA says it continued to work with authorities, such as the International Labour Organisation (ILO), to monitor progress in workers’ rights.

In a statement to CNN, FIFA said it was “undeniable that significant progress has taken place” in the country, and that the tournament was the “catalyst for these reforms.”

It did, however, concede that more work needs to be done.

“It is equally clear that the enforcement of such transformative reforms takes time and that heightened efforts are needed to ensure the reforms benefit all workers in the country,” it added.

The ILO published an updated report in November highlighting areas where workers’ rights have both improved and where they still need work.

‘There are so many memories’

For many locals, though, the World Cup was a time that will live long in the memory.

Last year, resident Reem Al-Haddad spoke to CNN about what the World Cup means to her and Qataris across the Gulf state.

Al-Haddad’s story was one of many to be included in the “GOALS” program – an initiative in collaboration with The Sports Creative, Qatar Foundation, Generation Amazing, and Salam Stores – which looked to tell the untold stories of the World Cup.

All of the individuals volunteered their time and told their stories with zero influence from the state, according to program curator Goal Click.

The 24-year-old spoke to CNN again, a year on from her first interview, to discuss what she felt the tournament’s legacy was.

“There are so many memories,” Al-Haddad told CNN, speaking about the joy of witnessing the World Cup in her home country.

“Like meeting all the new people and making new friends with the tourists that came, the cultural exchange and the way that tourists were in love with the culture.

“I don’t know. Everything about the World Cup was unforgettable. I think it was the best time.”

A year ago, with the tournament in full swing, Al-Haddad was reluctant to speak extensively about the widespread criticism of Qatar’s human rights record, instead wanting to focus on how soccer could be a unifying factor in healing cultural tensions.

Now, she accuses those who criticized Qatar of hypocrisy – referencing nations and organizations who she says have failed to adequately help Palestinians amid Israel’s war with Hamas in Gaza.

“I don’t understand how they’re using human rights just for the World Cup and now human rights are like nothing,” she added.

“As I said before, every country around the world has spots that they can advance in and I think Qatar is advancing in every aspect.”

She says a lot of tourists left the tournament with a new-found respect for both Qatar and the Middle East, adding that she’s seen a slight increase of visitors in the months since.

When asked exactly which areas she’s seen improvement in, Al-Haddad brought it back to sport.

She says the younger generations have been inspired by the tournament and says she sees more children playing soccer than ever before.

Al-Haddad also praised the influence the World Cup had on women in sport, adding that she’s aware of so many more projects which encourage increased participation in a wide range of activities.

“Even my cousins, girls and boys, who had nothing to do with football are now so interested in it and they memorize all the footballer names,” she said.

“I feel like it’s increased the love of football.”

The IMO said the World Cup was just the start of the nation’s sporting ambitions.

“The infrastructure now in place, including the stadiums, transportation and accommodation, combined with the successful planning and organisation of the safest and most accessible World Cup of all time, has affirmed Qatar’s credentials as a host for major sporting events,” it said in a statement to CNN.

“As part of the ongoing legacy, we aim to leverage our existing infrastructure to host additional events.”

It added that a detailed plan on how the stadiums will be reused is expected after the country hosts the Asian Cup early next year.

Sporting impact on the region

While the legacy of the World Cup will be disputed for years to come, the tournament has certainly opened up the game to a new region.

The World Cup is set to return to the Arab world in 2034, with Saudi Arabia the sole bidder to host the competition.

In recent years, the nation has hosted a number of major sporting events – notably in Formula One and boxing – while its investments in LIV Golf and the Saudi Pro League have arguably disrupted golf’s and soccer’s world orders.

Shortly after the World Cup final, Cristiano Ronaldo moved to Saudi club Al Nassr, triggering a wave of well-known names to follow suit. The league now has ambitions to grow into one of the biggest in the world.

To host the World Cup, then, would be viewed as a major coup for Saudi Arabia which, like Qatar, has frequently been accused of using sport to gloss over alleged human rights abuses.

Sports & Rights Alliance, a global coalition of nine human rights and anti-corruption advocates in sports, urged FIFA to secure human rights protections ahead of 2034 the tournament. Whether FIFA adheres to that call is yet to be seen.

It’s perhaps too early to nail down the legacy of Qatar 2022, off the pitch at least. A year on and there has been some improvement, though arguably progress has slowed down since the spotlight moved away.

On the pitch, the legacy appears more clear. Qatar 2022 is now being used as a blueprint for other nations in the region to host global sporting events.

And, with the amount of money on offer among the Gulf states, FIFA is not the only sporting organization now eager to explore new opportunities.