The demise of banking giant Credit Suisse sent shock waves through financial markets and appears to have dealt a blow to Switzerland’s reputation for stability, with one executive suggesting investors will now look at the mountainous central European country as “a financial banana republic.”

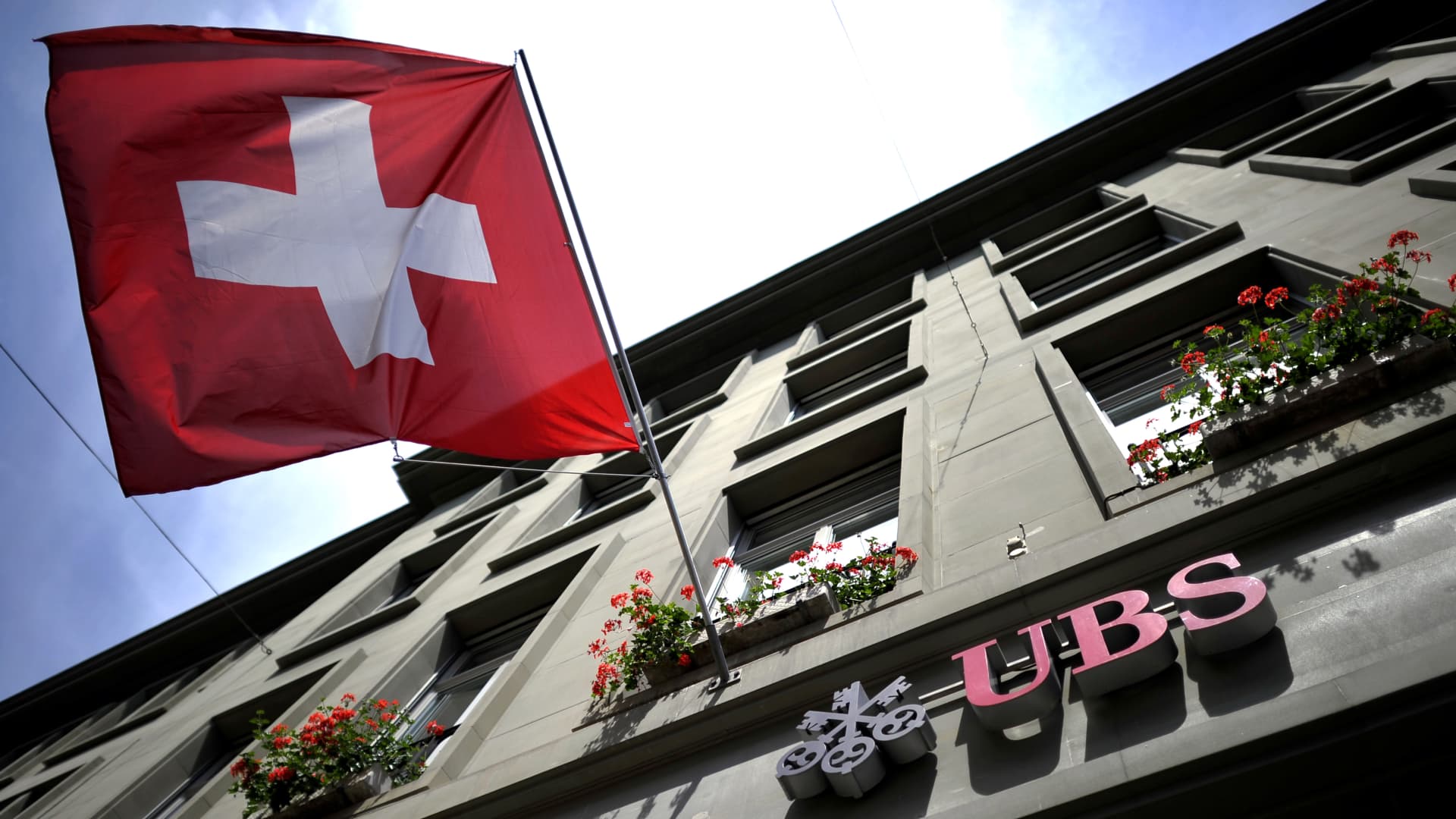

UBS, Switzerland’s largest bank, agreed on Sunday to buy its embattled domestic rival Credit Suisse for 3 billion Swiss francs ($3.2 billion) as part of a government-backed, cut-price deal.

Swiss authorities and regulators helped to negotiate the agreement, which came amid fears of contagion to the global banking system after two smaller U.S. banks collapsed in recent weeks.

The rescue deal means Switzerland, a country heavily dependent on finance for its economy, is on track to see its two biggest and best-known banks merge into just one financial giant.

“Switzerland’s standing as a financial centre is shattered,” Octavio Marenzi, CEO of Opimas, said in a research note. “The country will now be viewed as a financial banana republic.”

“The Credit Suisse debacle will have serious ramifications for other Swiss financial institutions. A country-wide reputation with prudent financial management, sound regulatory oversight, and, frankly, for being somewhat dour and boring regarding investments, has been wiped away,” Marenzi said.

A spokesperson for the Swiss regulator FINMA declined to comment.

Shares of Swiss-listed UBS on Tuesday rose 7.3% by around 12:50 p.m. London time (8:50 a.m. ET), extending gains after closing higher in the previous session.

Credit Suisse traded up 3.5% during afternoon deals after ending Monday’s session down a whopping 55%.

Under the terms of the emergency takeover, investors in Credit Suisse’s additional tier-one bonds — widely regarded as a relatively risky investment — will see the value of their holdings slashed to zero. It means investments worth roughly 16 billion francs will become worthless.

AT1 bonds, also known as contingent convertibles or “CoCos,” are a type of debt that is considered part of a bank’s regulatory capital. Holders can convert them into equity or write them down in certain situations – for example when a bank’s capital ratio falls below a previously agreed threshold.

“The extraordinary government support will trigger a complete write-down of the nominal value of all AT1 debt of Credit Suisse in the amount of around CHF 16 billion, and thus an increase in core capital,” FINMA said Sunday.

The unconventional move is at odds with the typical practice of prioritizing bondholders over shareholders when a bank fails and prompted turmoil in the market for convertible bank bonds on Monday.

Vítor Constâncio, who served as the vice president of the European Central Bank from 2010 to 2018, said via Twitter that FINMA’s announcement was a “mistake with consequences and potentially a host of court cases.”

The ECB and Britain’s Bank of England both sought to distance themselves from FINMA’s decision.

Here’s what’s driving the gains for gold as it approaches its highest levels on record

Bank panic created this pocket of opportunity with yields nearing 8%, analysts say

Market veteran says we may be ‘a long way from a new bull market’ and shares what to buy and avoid

European Union regulators, composed of the ECB, the European Banking Authority and the Single Resolution Board, said Monday that they would continue to impose losses on shareholders before bondholders.

“This approach has been consistently applied in past cases and will continue to guide the actions of the SRB and ECB banking supervision in crisis interventions,” they said.

The Bank of England echoed this sentiment shortly thereafter. “Holders of such instruments should expect to be exposed to losses in resolution or insolvency in the order of their positions in this hierarchy,” the BOE said.

“One feature of this whole banking pressure that we’ve seen over the last week or two is that actually yes we’ve seen major volatility in equity markets, major volatility in fixed income markets, and also commodity markets, but very little volatility in foreign exchange markets,” Bob Parker, senior advisor at the International Capital Markets Association, told CNBC’s “Squawk Box Europe” on Tuesday.

Asked about how investors might now think of Switzerland’s reputation for stability, Parker replied, “When I was in Zurich last week, this subject actually was a hot topic.”

He said there had been “some very modest” weakness in the Swiss franc against the euro in recent days, noting that this is the currency pair the Swiss National Bank, the country’s central bank, focuses on.

One euro was last seen trading at 0.9961 Swiss francs, weakening from 0.9810 when compared with March 14.

“We’ve moved back close to parity on Swiss franc-euro. So, I think to answer your question, yes, to some extent the Swiss franc as a safe haven currency has lost some of its allure. There is no doubt about that,” Parker said.

“Will that be regained? Probably yes, I would argue this is very much sort of a short-term effect,” he added.

— CNBC’s Elliot Smith and Sophie Kiderlin contributed to this report.