The year is 1984. It’s Super Bowl Sunday and you turn on the TV to see a procession of stern men marching through a tunnel. No, it’s not the Los Angeles Raiders. It’s the most important Super Bowl commercial of all time.

Apple’s iconic Macintosh advert, simply called “1984” and based on George’s Orwell’s novel of the same name, featured a “Big Brother” figure addressing hordes of subjects from a giant screen and a woman who escapes riot police to smash the screen with a hammer.

When viewed now, it is the epitome of the 1980s – CRT TVs, dramatic voiceovers and big hair. But back then, it was unlike any commercial America had ever seen.

“They sold $150 million worth of computers in 100 days,” says David Stubley – sports marketing expert and author of Gamechangers and Rainmakers: How Sport Became Big Business – in an interview with CNN Sport. “The whole ad industry just stopped in their tracks and went: ‘What just happened? How did that happen?’”

It might be hard to believe, but the Super Bowl was not always such a big deal. Long before Taylor Swift or the invention of the jumbotron, Super Bowl I was won, fairly comfortably, by the 1967 Green Bay Packers.

If you were one of the 24 million people watching at home, you would have seen halftime commercials from the likes of Goodyear, McDonald’s and Tang, each of whom would have paid a reported $38,000 for the slot – about $350,000 when adjusted for inflation.

By 1984, Stubley estimates that companies were forking out around $300,000, or $900,000 adjusted. That’s a sizeable amount, until you consider that the NFL is now selling some 30-second slots for $8 million.

It would be disingenuous to claim that “1984” is the sole reason for Super Bowl commercials now releasing with the fanfare that they do. But, as Stubley explains, there is a noticeable “before and after” effect around the iconic commercial.

“Advertising before that time was either cheesy, personality driven, or what I would describe as transactional – ‘Here it is, do you want it?’” he explains. “What this ad did, it basically said: ‘Forget everything that’s happened in the past. And the only way to do that is to smash that hammer through that big screen.’”

It is perhaps no surprise that the commercial was so cinematic, given who directed it. Ridley Scott had enjoyed so much success with “Alien” and “Blade Runner” by that point that many did not realize the Englishman had actually started his career in the advertising industry.

His signature dystopian style lent itself perfectly to Orwell’s story.

“We were all so scared about 1984, so it tapped into that brilliantly,” says Stubley. “Everyone thought the world was going to come to an end in 1984, if you’d read George Orwell’s book. And so to have this take on that whole scariness and confront it in such a brilliant way, I think it really caught people’s imagination.”

Despite the Macintosh computer never actually featuring in the commercial itself, it is hard not hard to infer that “Big Brother” represented the existing tech companies.

“The juxtaposition between the alternative of IBM and HP and Dell and this was probably what made it so exciting for everybody. It’s a bit like the Air Jordans 10 years later. You know, sticking two fingers up to the establishment,” explains Stubley.

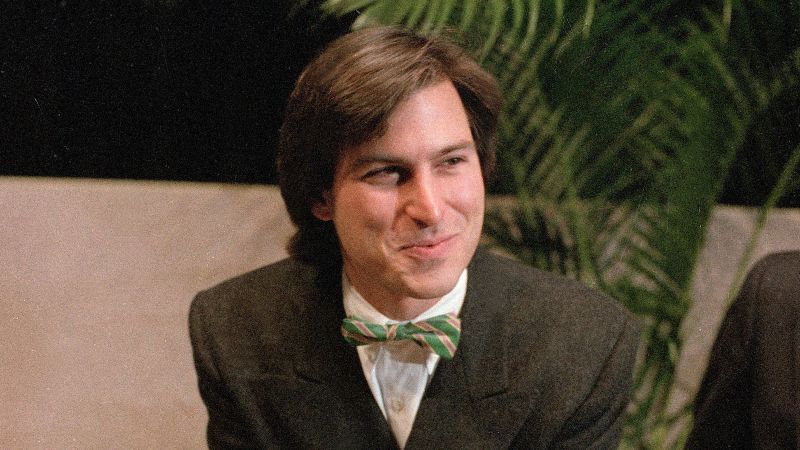

“Steve Jobs, if you look at any of his talks from that era, he openly stokes that. He says: ‘All these suits who just crank out vanilla hardware and vanilla software, there’s got to be a better way, surely.’ He was very good at saying: ‘That’s the establishment, that’s traditional. We’re nothing to do with that.’”

Handily for Apple, the 1980s were not only defined by Orwellian anxiety. They were also a decade when advertisers started to devote real attention – and budget – to the power of the little box in everyone’s living room.

“TV advertising at that time suddenly blew up. All these new categories suddenly discovered it,” says Stubley. “In America, there was this huge war between Miller and Budweiser. Then you had finance suddenly discovering the power of TV, retail discovering the power of TV. So all of these categories were all kind of piling in.”

It meant Apple were able to spend the kind of money – estimated by Stubley to be around $600,000 ($1.8 million when adjusted for inflation) – that was required for what was essentially a 60-second blockbuster.

Of course, you can spend all the money you want on the perfect Super Bowl commercial, but if everyone the next day is talking about the game itself, then the effects will be limited.

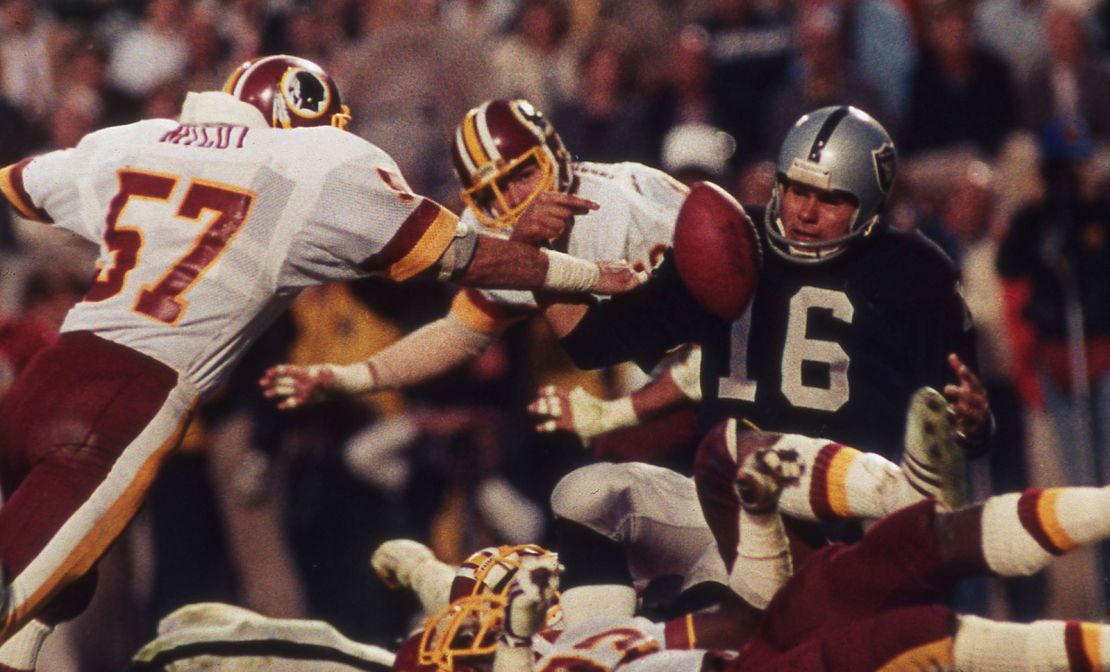

Luckily for Steve Jobs and co., that was not the case. With the Raiders up 21-3 on the then-named Washington Redskins at halftime, the contest was essentially over.

“All the action was taking place in the ad break, not on the pitch,” says Stubley. “You’re sitting there, it’s a dull game, you know what’s going to happen. You’ve got your beer, you’ve got your burger. You’re sitting through traditional advertising – Taco Bell, Walmart, whatever.

“And then suddenly, boom! This thing comes into your living room. It must have been shocking.”

The success of the Macintosh commercial, according to Stubley, prompted other companies to spend bigger on their own Super Bowl advertising.

“Post-1984 there was a lot of money to go around,” he says. “And so if you want to build rapid brand awareness (and) you’ve got a $400 million ad budget, as Budweiser would have had in the 90s, and you want to put Miller Light back in its box … you just buy up the ad breaks in the Super Bowl.”

Even now, when Super Bowl commercials come with a price tag of $8 million, Stubley still believes they can be a worthwhile investment.

“If you’re looking to build brand awareness amongst American adults aged 35 and under, the Super Bowl is one of the quickest ways of doing it, if not exactly the cheapest,” he explains.

But the halftime advertising landscape after the Apple commercial was not just defined by its ever-increasing budgets. Companies also borrowed stylistically from the way Apple approached the task. Nowadays, more than 40 years later, it is not hard to see the ripples left by “1984.”

Big-name directors routinely trade Hollywood for the Super Bowl, with the likes of Martin Scorsese, David Fincher and Zack Snyder all contributing commercials in recent years.

In fact, many halftime commercials are now mini movies in themselves, with A-list actors, storylines, and even teaser trailers released ahead of time. Many tune in just to watch the adverts, such is their cultural importance.

In the streaming age, when many people can watch anything at any time, live sports remain as one of the few ways advertisers can create watercooler moments.

“In today’s fragmented world, to still be able to get 120 million Americans – that’s not even the global audience – to sit in front of something, it’s quite breathtaking,” says Stubley.

“This is the biggest event in the advertising calendar, period.”

This year, when you watch Kendrick Lamar perform in the halftime show, it will likely be accompanied by a small Apple logo in the bottom-right corner – a privilege the tech giant paid $50 million for.

And if you find yourself laughing, or texting a friend, or just thinking about about any of the commercials you see this Sunday, spare a thought for “1984.” They might not exist without it.