Maya Ajmera, President & CEO of the Society for Science and Executive Publisher of Science News, chatted with Raj Chetty, an alumnus of the 1997 Science Talent Search (STS) and the 1997 International Science and Engineering Fair (ISEF). In 2018, Chetty founded Opportunity Insights, an institute based at Harvard University dedicated to harnessing big data to improve upward mobility out of poverty. Chetty is the William A. Ackman Professor of Economics at Harvard, a MacArthur Fellow and a recipient of the John Bates Clark Medal. Chetty, who recently joined the Society’s Honorary Board, sat down with Ajmera this fall for a fireside chat hosted by the Society. We are thrilled to share an edited version of that conversation.

Tell us about yourself and a little bit about your upbringing.

I grew up in New Delhi, India, until I was 9 years old. Then I came to the United States with my parents. I had what I think is a common experience for many immigrant kids: I saw the U.S. as a land of opportunity. Seeing the big contrast between India and the United States has shaped some of my perspective and interest in issues of inequality, social mobility and opportunity.

That experience, in part, inspired my research into what factors lead people to pursue careers in science and innovation. We found that America has many “lost Einsteins” — women and people from minoritized or low-income groups who could have made significant discoveries if they had been exposed to innovation as children.

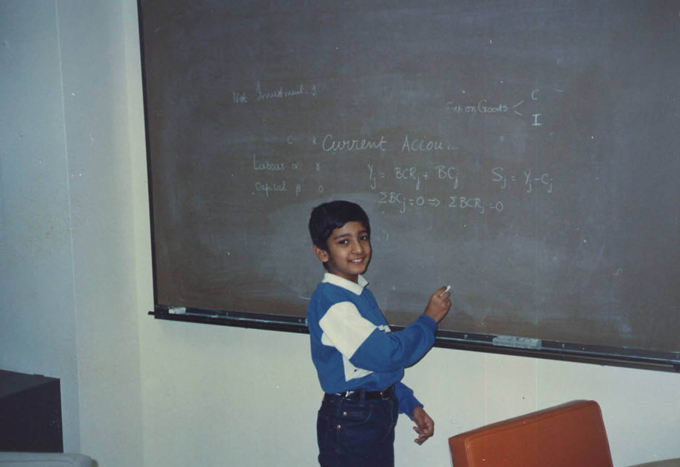

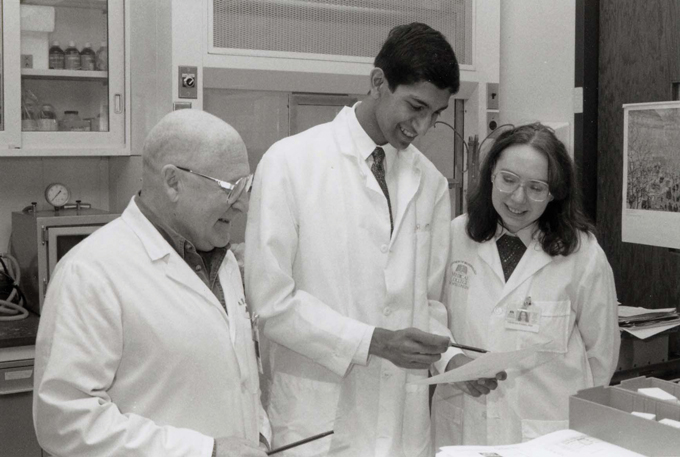

You participated in ISEF and STS. What are your memories of those competitions?

I have vivid memories of participating in ISEF and STS. I had an opportunity to work during the summers and after school at the Medical College of Wisconsin in a microbiology lab, which is where I did my research project. At ISEF, I remember being struck by the experience of seeing all these students from different parts of the U.S. doing lots of different exciting things. Conducting research in high school and participating in ISEF shaped my own interest in research and the types of questions I’m focused on today.

What inspired you to apply big data to the study of economic mobility?

In high school, I started to realize that I was very interested in research, science and discovering things. But at the same time, I realized I was more interested in statistical analysis of the data I was generating. My interest in math and statistics and my experience seeing vast differences in outcomes between kids in India and kids in the U.S. led me towards economics and social science. Big data came later. When I was in college and in graduate school, big data wasn’t a thing. But I later discovered that it could be a great vehicle to study some of the questions I and many others had been thinking about for decades.

You have studied a range of variables that both coincide with and challenge our perceptions of economic mobility and the American dream. What findings have surprised you the most?

What surprised me the most is how the U.S. is not actually all that much of a land of opportunity, despite that perception. If you grow up in the U.S. in a low-income family, your odds of reaching up into the middle class or beyond don’t look that great. In some sense, if you want to achieve the American dream, you are better off growing up in Canada or in many parts of Scandinavia.

But when I started digging further into the data on millions of children’s experiences from anonymized tax return data, it became clear how disparate opportunities are, depending upon where you live and the color of your skin.

For whom is the American dream possible?

In simple terms, white Americans growing up in middle class families in certain communities — often higher-income areas with better schools and better social networks — have great outcomes. We also see very good outcomes for many kids who come here as immigrants. But there are vast swaths of America, including much of the Southeast and many cities in the industrial Midwest, where even white kids don’t have great chances of rising up. For Black kids, unfortunately, and Black boys in particular, the American dream is not a reality almost everywhere in the U.S.

Your most recent research highlights the importance of forging relationships that transcend socioeconomic status. Can you tell us about those findings?

The vast differences in children’s chances of rising up across different communities became a motivating puzzle for our research: What factors explain why we’re seeing kids from low-income families do really well in certain parts of Iowa, for example? Is it about the schools? Is it about the types of jobs? Something else?

Over the years, many sociologists have discussed the idea that it might be about who you’re connected to, who shapes your aspirations, and what your social network looks like. But the problem was we didn’t have a good way to measure social capital empirically. With the advent of online social networks, I started talking with the team at Meta about the possibility of launching a large-scale collaboration between Meta and our research team to study these questions. We were able to use anonymized Facebook social network data on 80 million people and looked at their friendships in the U.S. — 21 billion friendships between them — and constructed very fine-grained measures, zip code by zip code, about the extent to which low- and high-income people were interacting with each other. Connections like these have turned out to be the single strongest predictor of differences in economic mobility that we or anybody else has identified to date.

We found that low-income kids growing up in communities where there is a lot of interaction across class lines have a much better chance of going to college and achieving a higher level of income. It remains to be understood exactly why that is the case, but we think it’s things like being aware of career paths they may not have otherwise considered.

What’s your favorite book?

I will go back to my childhood and say Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, which in retrospect, I realize is a book about upward mobility. I don’t think I had quite figured that out as a kid.

What’s keeping you up at night?

Knowing that the pandemic has made all the issues that we’re studying only worse. Finding solutions to these problems is all the more imperative with that in mind. Not just because the American dream in and of itself is important, but also because it has very important political implications. Democracy itself is at risk at the moment because many people feel disenfranchised. I would like to have more answers to the question of what we can do to make a difference. If somebody were to ask me how we can narrow racial disparities or improve outcomes for many low-income kids, I have a couple guesses but don’t really have the answer. I think that lack of scientific understanding prevents us from finding a solution. That’s the kind of thing that I often lie in bed thinking about and what I think makes social science so important and exciting.